Prose

A More Visceral Sense of Language’s Limitations

A Conversation with Leah Souffrant by Liesl Schwabe

A More Visceral Sense of Language’s Limitations

A Conversation with Leah Souffrant by Liesl Schwabe

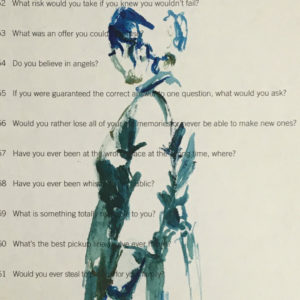

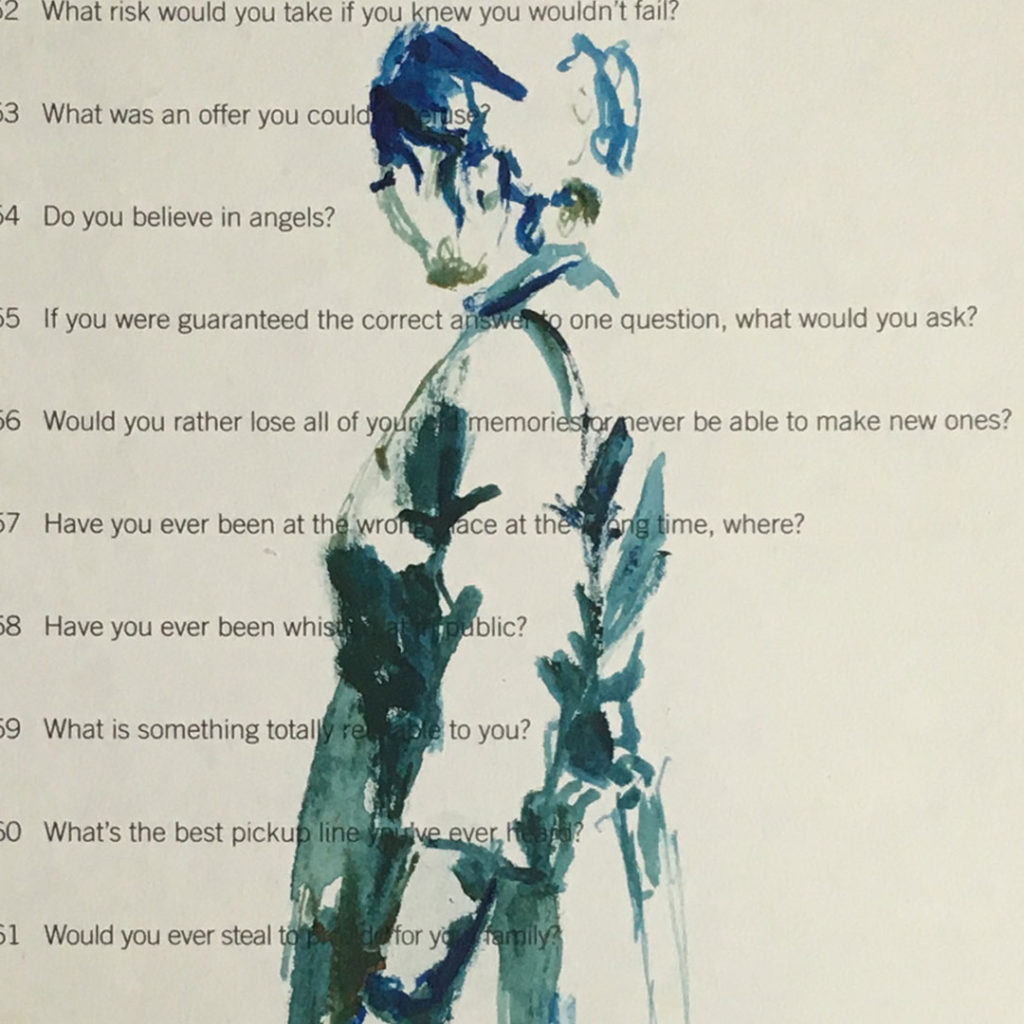

Images by Leah Souffrant

“Deciding to think is not the same as moving the mind to think differently.” So writes poet, critic, and educator Leah Souffrant in her lyric essay series “A Slowing.” In that piece and in her 2017 book Plain Burned Things: A Poetics of the Unsayable, Souffrant evokes what is often invisible, ignored, forgotten, or intentionally obscured. With a kind of alchemy, she uses language to illuminate something beyond language and, sometimes, the very limitations of language.

Over several years, Leah and I have connected as teachers, mothers, and writers, sharing an investment in the creative process – often asking how to scaffold it for others and how to safeguard it for ourselves. And so, when Leah began a visual art practice a few years ago, the move seemed at once organic and innovative, a continuation of the work she’d been doing all along as well as something altogether different. Recently, I had the delight of visiting her studio for the first time. Using newspaper transfer and other snippets of text, Souffrant’s visual work looks to, as she says here, “expose the entanglements that already shape us.” The following conversation, which took place both in person and over email, expands on that idea and has been edited for clarity.

In your writing, you explore erasure, memory, and the “unspeakable.” In what ways does your visual art capture or reflect what we don’t remember or cannot say? How does your art emphasize erasure in ways that are different from writing?

A curiosity about the limitations of language has motivated much of my work. Poetry dances with silence and all our sensations outside its words, sensations that build meaning and knowledge in ways words can’t. Even words describing a tender embrace in careful detail are only tender with the embraces we’ve felt, in our bodies, some memory of tender touches. If our experiences are limited, as when we’re young, stories can build some of those memories in us, constructed on what we do know, filled in by imagining. Poetry is a bit different than stories, at least for me. Poetry relies on what remains unsayable, what is not words.

I think of William Carlos Williams’ famous poem “This Is Just To Say.” The words sound like a note left in a kitchen, but the poetry of it is in how it reaches beyond the plums, beyond the story, to a whole feeling of tenderness and the imagining of routine thoughtfulness and mundane transgressions that feel like a relationship. If Williams put all those things on the page, it would become less and less poetic. I think of Rilke, his stunning poems weaving through love and loss, the Duino Elegies. Similar to the plums, the words swim in blanks, the unnamed, impossible experiences. […] When we read a poem, we expect or wait for or discover a moment when the poem opens up and points to something beyond its words. If it doesn’t do this, the poem fails, it loses its poetry.

I say all this to clarify some of my own long relationship to the unsayable in poetry. I have written (2009, 2017) about how artists – poets, novelists, filmmakers, painters -- rely on what is missing or absent or empty to convey traumatic experience especially, but I do believe this reliance on gaps is not limited to responses to pain or difficulty or trauma. In a sense, art – poetry perhaps most obviously – is defined by its relationship to the unsayable and its dependence on memory: of experiences, of feelings, of touches, fears, tears, sighs of relief, disappointments, kisses, and so on.

Increasingly, the spaces within poems have grown for me as a reader and writer, and my conviction that words are not only limited but often woefully inadequate has grown too. Inadequate for what? you might ask. Here I rely on another conviction, which is that arts teach us, that arts are essential for developing knowledge. The knowledge arts offer us is a growing sense of possibility (which serves imagination in other areas of importance), of imagination (to experience through the work what is outside our lived body), of empathy (when that imagining helps us understand some of what others do experience bodily), of heightened sensation (in the sensitivity to our response to the art, by provoking memory or emotion). Novelist Jeanette Winterson put it this way: “Art reminds us of all the possibilities we are persuaded to forget. Peace or war, we need those alternatives.” The imagining provoked by art is not catharsis, which implies a release, a discarding of something we held onto. It’s instead generative, “creative” in the sense that art creates something in us. A new memory, even of the art itself. A song we hear. A dance we watch. A poem we read. A painting we look at.

So, the arts broadly speaking offer us a great deal of significance, not just personally but societally. If you don’t believe that, then my discussion here may not make sense.

As poetry increasingly was stretching wider and wider, for me, the words themselves seemed often barely important. Trying to write poems feels like trying to explain the inexplicable. A futile effort. To write as I am here, in sentences, draws a reader through some of my thought process and my discoveries, through experience and research, meandering or abstract though they may be. But this is not poetry. Poetry demands the hollow spaces that will become hallowed. Poetry takes words as its medium to do something beyond words. But the expressions I was trying to reach in poems were getting closer to stories. Not that the writing was more profound, but just not finding shape in poems. It was frustrating. I wrote fewer and fewer poems.

When I turn to visual art, the relationship between words and that aesthetic knowledge lifts away a bit, making room for the generative, creative experience. I am often moved by language, and words are a consistent element in my art, but the relationship to the words is indirect. The words in my paintings “evoke” something or provoke a shift in attention as they’re discovered in the painting, but they aren’t posing as complete. The unsayable of poetry is visible in the illegibility of some words. The incompleteness of language’s communication is underscored by its proximity to color, texture, and figures painted on the same surface. Words are not enough. They never were in the poems, but visual art offers me a more visceral sense of language’s limitations.

In some of my paintings, you can’t even read the words. You see them, but they’re illegible. Words are all around us, even when we aren’t actively taking them in. And words shape our lives. In other paintings, the words come to the fore, easy to read, but even then they mingle with the images, become part of the visual elements. It’s not possible to respond to the meaning of the words apart from the meaning evoked by the images they’re with in the painting. This, perhaps, exaggerates what I believe about poetry in general: it relies on what is not words.

As a poet, you write a lot about “entanglements.” (In fact, that’s the title of your second book!) In both the form and the content, your prose illuminates a kind of interdependence. Connecting historical events and present day tendencies, threading the quotidienne with larger social context, your writing also, at times, includes or even implicates the reader. We are, in other words, entangled with one another as a result of your writing and our reading. In your visual art, is there a similar impulse?

The short answer is yes. I have a few pieces that draw from explicitly current-event imagery – photos of pedestrians in Wuhan in early 2020, paintings of protesters in Oregon in summer 2020. But in every piece I make, even the most abstract works, I’m aware of the ways we get enmeshed in what we’re looking at, the ways bringing together different elements – text & image, say – makes them interact with each other, entangles them. For me, this is a way of exposing the entanglements that already shape us, already push us to make meaning, whether intellectually or emotionally or otherwise, through memory or mood or association with a time or place or person.

In 2020, I made two pieces with the words “Nothing Lasts Forever” centered. One of them is words on canvas, black and white, but the timing of it during the middle of the pandemic, for me evokes that time, and the plain blur of that piece relates to the uncertainty and blur of the pandemic. The piece almost seems incomplete, but it’s perfect. The other piece I made with the same words is a small construction of two crossed pieces of wood, and the words hover over an image of a child running away down a city street. To me this image is joyful and a bit heartbreaking, but regardless of how it comes to you, the words here evoke childhood or nostalgia or something like that. Same words, different image. This is a very obvious illustration of what I mean by association. In some cases it comes from you, the viewer, in some cases its guided by the piece, and usually there’s a bit of both, entangled.

Art works this way all the time, I think, but in my work perhaps it’s exaggerated because I’m so interested in language. Art draws us in with its form – color, medium, size, you name it – and its content and these mingle with what we bring to looking, deliberately (perhaps through study, for example) or by accident (perhaps through our mood when looking). Art is always a mind-body experience, not one or the other. We see a painting or hear a song with our bodies, our senses, but we don’t leave our minds out of it.

I try to activate that interdependence in my work. One series I started in 2019 is painted on pages of a book called 3000 Questions. It’s the kind of book designed to inspire writing and reflection for people who may need inspiration, or it could be used to provoke conversation like a Would-You-Rather game. Some questions are silly or simple and others are more thought-provoking. “Do you like comic books?” and “If you could live forever would you want to?” and “What promise do you know you’ll never break?”

On these pages I’ve painted a figure, a painted sketch. The body language is specific, but the face is not, yet they each come through as people, individuals, not just types. So these sketches might evoke a contemplative person or a standoffish person, for instance. And behind the figure we see the lines of questions, some clear and some obscured by the painting. At first they might seem like just a pattern, a background. But this composition may be the most deliberate effort to clarify that sense of entanglement. We see the figure first, from farther away, bring in blue or green paint. We see the posture, the body language, and we respond to that. We interpret it, even if absentmindedly. Then, upon closer inspection, we lean in. If we read the questions then the image changes, even if subtly. We can’t look at both the woman gazing off beyond the frame and read the question “Do you believe in angels?” without stitching the two together. It may be a sense of contrast or juxtaposition – a silly question paired with a serious stance – or intensification – a profound question with a serious stance. In any case, once the words reach your thoughts, the image changes. How you see changes.

You include text within your art, notably newspaper headlines and snippets of articles. Yet these are also often obscured and layered. The point is not that we “read” the newspaper. So how does this text function in your work?

The newsprint functions in multiple ways simultaneously, another example of the entanglements: various, shifting, personal. “The news” evokes current events, immediacy, the here and now. If something is in-the-news, then it’s topical, timely. The study of ancient Egyptian civilization is not news, but the report of a newly discovered ancient tomb is news. News is all of the stuff shaping our social and political and cultural world right now, and we’re in that now even if we aren’t dusting the sand off the sarcophagus ourselves. It’s news.

So I make gestures towards that nowness by including newsprint in my works, but more importantly it is background; it is obscured by color and image, by the experience of the art. So that “news” is there, but it’s not what the work is “about.” And I deliberately obscure it or let it be obscured by my process of working the canvas. I transfer the ink from the print itself onto the paint, so the words are inverted, appear in mirror image. I’m still able to read them easily at a glance if they are transferred clearly, but different viewers may have a different experience of processing the inverted letters. But the words are partial, often obscured by paint or only faintly visible. They aren’t meant to be read as text.

In most of the pieces, columns of newsprint become a pattern rather than readable text. The columns create texture in the work, as the news in our lives is a kind of background or texture – sometimes faint, sometimes intense. And finally, I draw poems from the language of the newspaper, isolating words and putting them together on a canvas to build or control associations. If the word “love” appears clearly on a canvas, it leads through in a particular direction, a different direction than the word “failure” or the word “loss.” And if “love” and “failure” both appear? They affect each other. I’m finding poetry in the printed word and offering it as a prompt to the viewer. And these words intersect with other elements of the painting too. In a painting of bold, messy colors, I read “love” differently than in a muted, pale field of color. And in nearly every piece, that noise of the news is a background. Even love is enmeshed with that world: social, political, cultural. It may have less “romance” but not less impact or power.

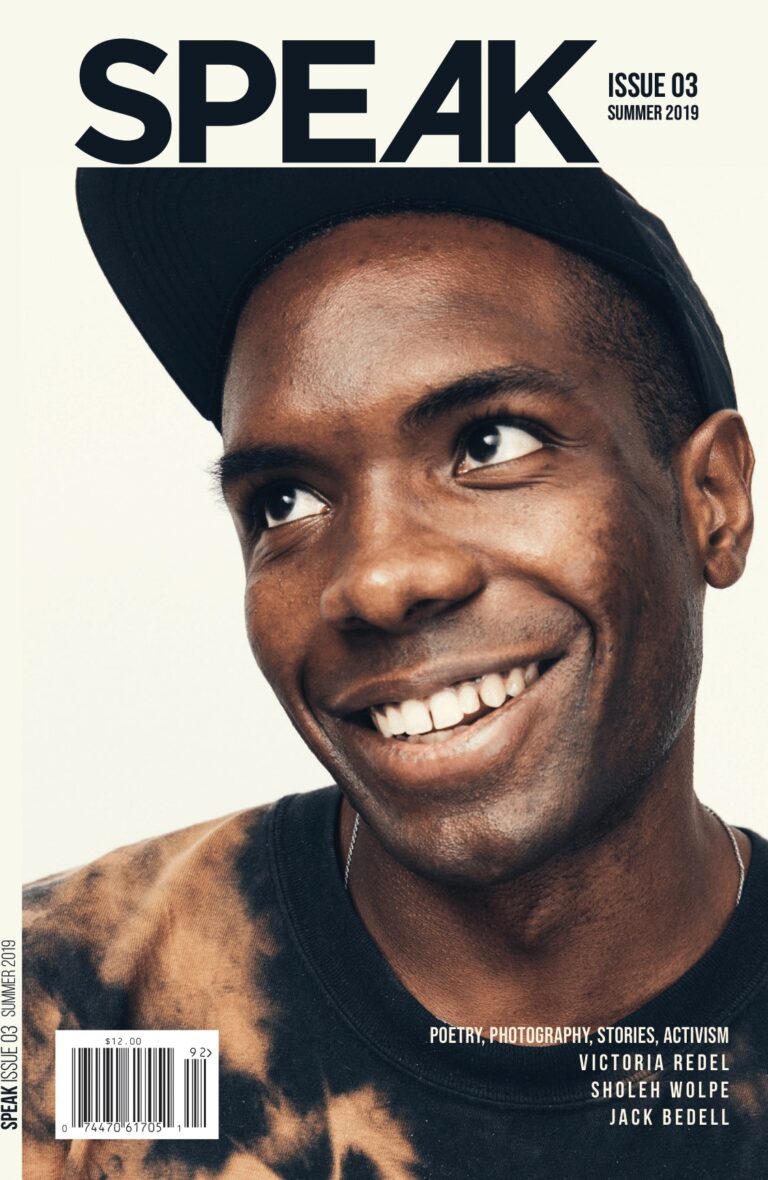

meet the author

Leah Souffrant

Leah Souffrant is a poet, essayist, and artist committed to interdisciplinary practice. She is the author of Plain Burned Things: A Poetics of the Unsayable (Liège 2017). Souffrant has received the New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in Poetry [...]

meet the author

Liesl Schwabe

Liesl Schwabe’s essays have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Words Without Borders, Creative Nonfiction, and The Rumpus, among other anthologies and publications. She served as a 2018-19 Fulbright-Nehru Scholar in [...]

Read More

More From Author

Subscribe to our newsletter