Amit da, thank you for taking the time to talk to Speak. I read somewhere that there was a time when you said you used to romanticize Kolkata. Would you still say that now after living there for twenty years?

I moved here in 1999 but I would say that I am not a very romantic kind of person so I don’t think I romanticize Kolkata. I have a particular take on it, on why I am moved by it, especially when I was growing up in Bombay and I used to visit Calcutta. And that for me has to do with being moved by an expression or manifestation of urban modernity. Modernity which for me is synonymous with what was so important for me as a child. When I speak of modernity I mean simultaneous dereliction and energy, the simultaneous ebbing and generation of life within the parameters of meeting and separation within a city where the next neighborhood or next street might feel stranger than an alien country and that is the kind of the paradox of the modern that I discovered in Calcutta and that is the reason I used to be very moved by it. I don’t think that Calcutta exists anymore. I think what exists now possibly has its own logic and its own sort of way of inheriting its past history, that it is more than a shell but the problem is that people who live here treat it like a shell and have stopped really engaging with what it means to live here and that I do find disappointing.

How would you define this engagement and contrast it with what used to be there before?

What I mean is that there is a sort of a denial of the city, a denial of any imaginative engagement with its history. So Kolkata in the sixties was a troubled city. It wasn’t that it was a cleaner or a less dysfunctional city than it is today or more streamlined but the spaces of the city were not only inhabited but I think they were imaginatively engaged with, now the spaces feel abandoned not only because the civic bodies don’t really govern these spaces but because there is an imaginative abandonment of what these spaces mean, as though people are denying the very idea of these spaces. They are thinking almost of Calcutta as a place to leave or move away from so it produces that kind of denial.

Do you think that could be due to the harsh realities of everyday life here?

It is also related to imaginative failure. Living in Kolkata was never particularly pleasant, living in New York in the 60s was not pleasant. Whether or not you engage with something intellectually and imaginatively is dependent on what’s happening in the culture. You don’t begin to engage in things when reality becomes smooth and pleasant. That doesn’t have anything to do with it.

So Calcutta was never a quarantined space in which the bad was filtered out and only the good was kept. Nor have any of the most interesting cities been quarantined spaces. Nothing interesting happens in the quarantined spaces. But I think Calcutta right now is unable to deal with its own spatial and experiential dimensions, that it looks away from them, in a way that it didn’t earlier.

It brings to mind the work you’ve been doing with trying to keep alive a certain element of the heritage that is reflected in the buildings, and I was wondering if you wanted to tell us a little more about that.

Sure. Of course there is a problem to do with the fact that there is a heritage list which is really woefully inadequate and which should be a much more comprehensive and longer list. And there is a problem that the buildings on the heritage list are not safe, that buildings are de-listed by the kind of bodies like the KMC, the Kolkata Municipal Corporation, heritage committee, which should be protecting these buildings, delisted and then destroyed. So there is all of that. But what I have been more concerned about, or equally concerned about, are the neighborhoods with comprise buildings which are not on the heritage list. So I am interested in the way we inherit spaces and buildings. Go beyond a narrative list of heritage. I’m interested in that moment of modernity which led to creating music in Kolkata and film and a way of seeing, and also life and literature. Also the spaces in which people live. And those spaces and those neighborhoods which comprise not some kind of inherited antiquity or some kind of monumental past made up of the great landmarks, but the seemingly ordinary but, on second glance, quite unique buildings of that period of modernity which made Calcutta so singular. I think those neighborhoods are on the verge of disappearing. It’s like the Bengali short story disappearing, or Adhunik songs. So the question is can these be retained and reused. Can an engagement with them generate some kind of new way of looking at the city. Can we reengage with Calcutta’s history? We have been denying its present but we have also been denying its past. Its past is the past of its modernity. Looking at this past, we are not talking about some utopian past in ancient India. We are talking about the past of our immediate forefathers who were ordinary people. We have almost no connection with them anymore, the world and ethos of those people: they are impossibly alien, like a species that’s vanished almost without a trace. Is it possible to re-engage with that past in a way that is not nostalgic, but in a way that is imaginatively rich and leads to a reassessment of what Calcutta is, who we are, and goes beyond a kind of lip service to Tagore and Tagore songs and things like that.

I keep coming back to the realities of living in a city, because I love to visit there when I’m homesick. instead of Pondicherry where I grow up. I keep coming back to the harsh reality that the common man in Calcutta struggles for hours to even get to their workplace. I think a big part of thinking of heritage and preserving beauty and ethos is that the common man does not have the time or the energy to engage with that.

The common man is very interested, not just in the static ideas of heritage but in the life around him. I’ve spoken with many common men and women, and they’re deeply interested and they don’t want to see this go to satisfy the greed of developers alone. The greed of developers does nothing to ease the life of the common man. Helping the life of the common man is not incompatible with retaining and re-using and rethinking our history and the way we think of the city. Besides the extremity of experiences that the common man has to go through, to use your phrase, “the common man, in Calcutta,” I think that returning from Karachi, which is a wonderful city with a wonderful intelligentsia and a set of very cultured people. I was still struck by how functional Calcutta is, that its dysfunctionality partly comes from governmental corruption and public and private apathy, but also takes for granted a certain freedom that is a characteristic only of functional cities. In Karachi, you cannot move from one place to another without fear and without being escorted by an armed escort. There are certain roads you cannot take, you cannot go on walks. The same is true of Johannesburg, the same is true of Mexico City, the same is true of places in Brazil, the same is true of New Haven. If you stay in New Haven in the hotel called The Study, if you go in one direction you move toward chic bookshops and cafés. If you move too much in the other direction, you’re in an area where you are in danger. And in Calcutta we do not have that. At once we have a kind of dysfunctionality which is also functional. Returning from Karachi, I realized how much we, which includes rich people, middle-class people, the working class, how much we have in that we can go where we feel like. I returned from Karachi, and I went to my in-laws’ place, walking with my wife in front of their building, near Ekdalia, at eight o’clock in the evening, two working class men and a woman were talking to each other, and it struck me that we had an extraordinary freedom which is certainly not the privilege of every city. And many things that I abhor and see as failures in governance, that are the result of corruption, I began to see on another level as a kind of amazing functionality. Near my in-laws’ house is the Gariahat flyover and under the flyover is a kind of mini township of homeless people, and whatever distress the homeless people may face, and whatever thoughts that people around them might have confronted with the homeless, it’s true that the people passing by there in the dead of the night are not in any imminent danger of being attacked by them, and nor are they in any danger of being attacked by people passing by, although the homeless are of course vulnerable to being uprooted by governmental dispensations that otherwise ignore them. So there are great fundamental forms of freedom and civility in Calcutta which are not to be forgotten. So the city also has, so the city should remember, the great kind of civility running through it. And what it has done is somehow disengaged from itself, it will not look at itself, it will not see what it is.

That’s beautiful. Thank you. I was also thinking of moving onto your activism, about the symposium you started in 2014, the literary symposium on literary activism. I was curious about your take on what is literary activism, and a little bit about that symposium

Literary activism is various things. It’s an attempt to bring back the terms of discussion about literature into a discussion of the open-endedness of literature and connect its value to something beyond its market value. Open ended about what that value is. But market value is imposed extraneously. The value of literature is not to do with the market nor is it sociological. It’s the most open-ended domain of thought and practice, creativity. Which is its value. The aim of literary activism is to discuss its curious, ambivalent value, to wrest the language of valuation from the market, which is what publishers and agents, and what many of us practice, when we speak in terms of commercial success. A publisher today will never say that this book is a masterpiece or it’s great work of merit and art if they believe it will sell 500 copies. What they mean nowadays when they say it’s a masterpiece is that it is going to be a commercial success. That’s what they mean, but they’ll never use those words. They will say that it’s a masterpiece. They’ve appropriated the lay language of criticism, of literature, taken it away from the literary departments who have not been interested in literature for a long time but have been interested in sociology and the operations of power and have remained largely muted about the operations of the market. Literary activism involves being aware of these movements and shifts in language and in the cultural landscape, and by being aware to open up a different space. That space is neither an academic space—it’s on the fringes of academia—nor is it a space such as the literary festival is, which is where authors basically speak about literature in the context of plugging their latest book. So it’s neither that kind of space such as you see in the literary festival, nor is it the professionalized space of the academic conference. It is a space that somebody invited to one of the symposiums, a philosopher called Simon Glendinning, called “a space for misfits.” Among various things, it’s a space in which academics, writers, thinkers, poets, translators, publishers, musicians, artists, can talk to each other in a way that’s deprofessionalized. In a way that’s not a professional response. We talk to each other about things all of us are exercised by but cannot speak of in professionalized domains where we have to curtail or censor certain subjects, and we are only led by certain themes and have to adopt a certain tone. Nor is it that domain of the fake celebration which is the literary festival, where you always have to be celebrating and speaking in a celebratory manner, without ever interrogating yourself or expressing unease about where you are. This is a space where you can confess to unease, about being where you are or what you are doing.

I was taken by literary activism, discussing that the pen is mightier than the sword. The times we live in now in America. Where are the voices that can create a movement? Is there any space for what you called misfits? We can’t find that, when we speak of agency, I know you want to speak it, but isn’t that market what gives agency to the misfit? I don’t know how we would counter that. Market is what gives a certain kind of voice to the writes, and don’t you think the misfits need that to get their voice heard, that without the market and distribution, no one pays attention to what they have to say? Every writer needs agency, whether it’s a blog or a book or a publisher.

But I don’t think the market gives voice to writers, it gives voice to themes that are commercially viable. And it has a very narrow understanding of what that is, and no understanding at all of what lies beyond the realm of commercial viability. Historically so much of value has been done outside the realm of commercial viability and success. Success only recently has become the preeminent dominator. Before the free market took over, one was allowed to learn from various things including failure. So I think we’ve forgotten that, we tend to not remember what happened once. Literary activism is also an attempt to try and remember the habits of thinking that have been erased from us.

In this discussion, Oprah Winfrey is a force for social or literary change, because of her clout with her book club, and there’s Baldwin. Wondering if you can think of any writers, the misfits, who have brought about any sort of social change. Since everything is now considered fake news, it’s a fight every day to have your voice heard.

There have been all kinds of writers who have made moves and opened up things for the sake of making this thing called literature or other writers understood in a new way. It’s too broad a subject for me to cover right now. I can think of one writer who we might consider too mainstream, but we forget that he brought many writers who are not in the mainstream to our attention, in the last 20 years. I mean Richard Ford, who has made us look again at figures like James Salter and Walker Percy and Richard Yates, I’m talking about twentieth-century American literature, and even made us look at forms like the short story and the novella. And works like “The Rich Boy,” by Fitzgerald, as great a work as The Great Gatsby. So Ford, though he seems establishment and mainstream, made certain kinds of shifts in our understanding of contemporary American writing.

Do you still hold to not giving tips and not giving anything centrality?

I do hold to that, because I believe in the moment. And if you believe in the moment, then you believe in something that is not there for more than an instant. And if you believe in the possibility of the moment, then you cannot believe in an overarching centrality or a hero, because change becomes the constant, and flux becomes the constant, and all the surprise and meaning of life and literature are dependent upon this constant state of flux and change. And all the difficulty of writing is that we cannot just reach for language, because nothing is pre-made, everything changes from moment to moment, and so we need to rethink at every moment in time what we are thinking and writing about. If there are no identical landscapes or faces and even the same face is different in different locations and at different times during the day, we have no choice but to be constantly thinking about words when we use them. We cannot say that we have a stock way of describing the person, because the person is a fluid entity. Concepts are also fluid entities, they are open-ended. That means that immediately that centrality, or the idea that there is a fixed point, there is a fixed hero who we can recognize immediately and whose story you can tell, becomes a kind of closed concept and you have to let go of those crutches and submit to the open-endedness of the experience. It’s because of the importance of the moment to me, partly because of that, that I’d say give nothing centrality. Centrality depends on a static idea of the present and the past and the future, as clearly distinguishable and recognizable. That also is a renaissance inheritance where we always put the human at the center of things, and everything else that is part of a theme in which the human is central becomes important only inasmuch as it is part of the story of the human being or helping to advance that story in some way. But what if each one of these things and objects in the room where the person is standing also has its own life, which is what I believe them to have, then we begin to see the constraints of that one idea of centrality, then we begin to think that surprise and energy and power radiates in various directions. A human being is only one point in a story made of various points.

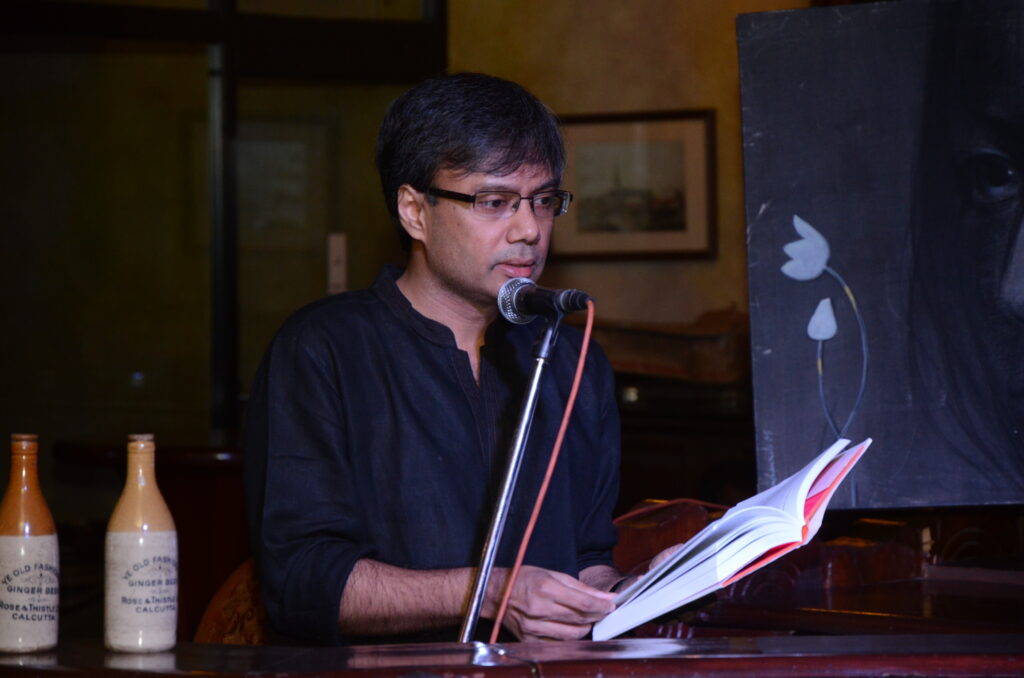

meet the author

Amit Chaudhuri

Amit Chaudhuri is the author of seven novels, the latest of which is Friend of My Youth. He is also an essayist, poet, musician, and composer. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

share

Read More

Subscribe to our newsletter