Each minute we breathed the plane cabin’s stale air took us farther away from the desert. I cursed every scratchy flight-crew announcement; gentle turbulence felt like rockets. When Marines staggered to the bathroom, their hands on my seat-back jolted me from thoughts of Jack.

We stopped to refuel at Ramstein Air Base in Germany. I crossed the terminal, stomping blood through my clotted calves, and shut myself in a metal bathroom stall. Old paint flaked from the wall; the latest coat shone hunter green. As my trousers hit the deck, I looked to my right and saw a roll of one-ply toilet paper. Gone was the need for the ziplock stash of chow-hall napkins in my cargo pocket. I choked up with relief. From here on out, there would always be toilet paper.

After shuffling and seat belts and more airline food, our plane’s wheels touched down in California. I landed with an inner scream. I banged down steel stairs onto concrete and stumbled through a receiving line of elderly veterans. Six of them had come out to shake our hands as we debarked. They wore red USO jackets and yellow-ribbon pins. I submitted to their wrinkled grips, feeling unworthy of their respect. On a table in the terminal lay an assortment of cell phones for Marines to call their families. I didn’t call anyone. The USO cared for us well, but I wanted none of it. It would take me two days to call my family.

On base I smelled the beach as we waited to turn in our weapons. The air felt liquid, compared to Iraq. Everyone else in the desert-camo queue jiggled with anxiety. They couldn’t bear the delay until they saw their spouses, who waited for us a ten-minute drive away. But I didn’t mind. There was no husband, not even a boyfriend, waiting for me. The closest substitute was back in Iraq and married to someone else. My roommate Nell and my childhood friend Maddie would meet me at the parade deck. After sliding my pistol through the armory’s barred window, I felt naked.

We rumbled to the parade deck in a white government school bus. I blinked into afternoon sun as my boots hit the asphalt. A crowd of balloon-holding, sign-wielding families surged toward us: a human rainbow exploding after seven months of brown and gray. A corporal from Data Platoon, sunburnt beneath a white-blond buzz cut, kissed his girlfriend. Nell jumped out with flowers, startling me, but I appreciated her enthusiasm. Behind her stood Maddie, the one who’d lamented in a letter that she couldn’t send me a vibrator. I hugged them both. Together, we searched the rows of seabags for mine. I tottered under two, a walking mountain of ripstop nylon.

As Maddie walked me to her Honda, she offered McDonald’s chicken nuggets and a snarky giggle. “So, what’s his name, Jack?” she said. She’d read my mind. As I buckled my seat belt, I said, “I shouldn’t worry about this, right?”

She paused, gripped the Civic’s stick shift, muscled it into gear. “Nah, man, don’t worry about it,” she said. And in the New York brogue of our childhood, echoing our weary mothers as they’d kicked off tight pumps after another day crunching shoulder pads against Wall Street suits, she shrugged, “whaddaya gonna do?”

I had no idea what I’d do. I didn’t yet know that my workaholic stoicism, punctuated by spirals into shame and self-condemnation, obscured just how common experiences like mine were in war. And it would be years before I learned the term—moral injury—for combat-zone transgressions of deeply held moral beliefs.

I acted on instinct my first evening back, unhooking my seabag’s clasp alone in my room. I hadn’t bought any furniture yet, so I sifted through my pile of camouflage and laid out my unwashed green sleeping bag. I cued Fire and Rain on my laptop, lay on my back, and closed my eyes, sniffing my gear in vain for the desert. My civilian belongings felt alien, with one exception: I curled up in that sleeping bag with my old pink blankets.

• • •

We all sat through a week of mandatory health screenings and readjustment seminars—don’t-drink-and-drive and don’t-beat-your-spouse and welcome-home speeches and paperwork. I slouched, knees wide and arms folded, in the freezing base theater, and took the lectures no more seriously than the navy doc’s questionnaire on TQ. My nightmares—buckets of bloody limbs—wouldn’t begin for another two months. And I wasn’t about to admit my feelings of massive guilt or breathe a word of my surprising longing to be back in a Groundhog Day routine, where contractors fed me and washed my laundry, where I could stand my Systems Control watch blindfolded, and where I was ten minutes’ walk from Jack. He felt like the only person with whom I could talk about Iraq. I knew I’d see him again in November, at our battalion’s formal ball for the Marine Corps birthday.

I didn’t call my parents right away. My official excuse was that my cell phone had died while I’d been gone, and it took a couple of days for AT&T to mail a new one. But the real reason was that I relished this time alone. When my family asked questions, I felt something akin to emotional asthma, unable to explain the depth of my feelings for a reality they’d never encounter. There was no way they could understand the satisfaction of a successful fiber optic repair job, the backslapping vibe of an evening brief, the weight of a transport case, or the surreal beauty of white smoke in an orange sky. Their questions—“Are you glad to be home?”—only grated on my nerves. Yeah, duh, I was glad to be home. But I also felt a surprising nostalgia for a vibe I couldn’t quite put into words.

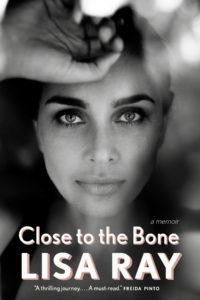

Teresa Fazio’s writing has been published in the New York Times, Rolling Stone, Foreign Policy, Washington Post, and The Nation, as well as the anthologies Retire the Colors, The Road Ahead, and It’s My Country, Too. She is the recipient of the Consequence Magazine Fiction Prize, the Sven Birkerts [...]

We only ship in UK, USA and Canada.

For deliveries in other locations please write to us at: editor@speakthemag.com