In North Kolkata, colossal old buildings tower over shrill, impatient traffic and rutted sidewalks lined with piles of green coconuts, tailor shops, and the occasional goat. Often the length and width and height of a city block, the enormity of these buildings is hard to overstate. Layered with tiny leaded windows or long wooden shutters and crisscrossed with electrical wires, these are the former homes and offices of the vast network of Bengali administrators and zamindars, landowners, on whom the British relied when Bengal was the wealthiest province of the Empire.

Centuries of coal smoke, monsoons, diesel exhaust, and neglect, though, have since obscured what was once regal. Intricate ironwork grilles and balconies remain, but entire mansions have faded to dingy, naked concrete. What takes your breath away is not the splendor but the residue of splendor. The dissonance of regarding something at once so imposing and so abandoned. Elaborately constructed and thoroughly overlooked.

And yet, the beauty of these buildings persists in a way that, collectively, is almost human. In the English translation of Chowringhee, a 1962 Bengali novel centered on the inner life of a grand hotel, the narrator, a clerk, describes Kolkata as a “hag.” But I would argue that while the city is no longer in her youth, her elegance prevails.

Sometimes, in the bright, tropical humidity, trees grow along the outer walls, taking root sideways, in the mortar or off some crumbling veranda. Erupting out of the decay, these scrubby branches and creepers expose the determined vitality of the city. Of life’s dogged resolve to reach for the sun from the unlikeliest of places.

I am an American currently living in Kolkata on a research fellowship, along with my husband and our eight-year-old daughter. Though I’d regularly spent time in rural India for over twenty years, I had never been to Kolkata until a few months ago. When we moved here.

Formerly Calcutta, the city was officially deemed the capital of colonial India in 1772, though by then the British had been expanding their presence across and their profits from the subcontinent for nearly 200 years. But 1772 also saw the birth of Ram Mohun Roy, son of a wealthy Bengali Brahmin, who learned Persian in Patna, Sanskrit in Benares, and eventually polished his English in London. A French Revolution enthusiast, Roy voiced some of the earliest challenges to British rule and fought against the most oppressive Hindu traditions, including sati, widow burning. He built schools, established newspapers in Bengali, Persian, and English, and advocated for freedom of the press.

Though Roy died in 1833, his efforts of providing voice to the people laid the groundwork for the independence movement that gained momentum and focus over the subsequent century. In 1911, the British moved their capital from Calcutta to Delhi in attempt to weaken, or at least create distance from, the opposition to colonial rule that was fiercest in Bengal. And it was this culture of protest – of newsprint and poetry, of revolution and resilience – that intrigued me.

I’d heard, too, about Kolkata’s stubborn resistance to the slick haste of the unrelenting future.

That the city carried on as this urban analog outlier. Where the currency was not monetary but a different system of value altogether. That of Tagore songs and used-book stalls and sickle and hammer graffiti. Of slow, sweaty days of time to think. If the rest of the world wanted everything instant and sterile, Kolkata, I wanted to believe, endured as the soulful antidote to the 21st century.

For all these reasons, I daydreamed about the city for years, and as with all fantasies, the imaginary pointed at something honest. In this case, I was wrong to pretend that anywhere might be immune to suffocating pollution or the crane-laden horizons of haphazard development or the arrival of Taco Bell at the mall. But I was right that, in Kolkata, the vastness of history seemed closer, more insistent, than what was to come.

Indeed, men with typewriters waited along Rash Behari Avenue, eager to conduct your correspondence for a small fee. Yellow ambassador taxis crowded the streets, the Tollygunge-Ballygunge tram staggered along, and ice deliveries came by bicycle, slick, glistening blocks like gems melting on the wooden cart. Surrounded by fourteen million people, I got the sense that we were all more beholden to whatever happened before than to what might never happen tomorrow, whether earlier this morning or a hundred years ago.

But rather than reassured, I was struck by an almost physical dizziness. Not nausea but uncertainty. Pausing to deter an ant while chopping an onion in the kitchen, I wondered what month it was. Walking to pick my daughter up from school, I stopped to let a motorbike pass and was seized with doubt that I’d paid the rent – either here or at home in New York City. Managing the basics of existence – electricity bills, school fees – I often caught myself not just searching for the date but adrift without any notion of time at all, not the season, nor my own age.

For a while I assumed this was the result of upholding a life on two continents. My husband was ordering kitty litter for our Brooklyn cat from our South Kolkata living room. My teenaged son, who stayed in New York, occasionally texted in the middle of the night to ask about things like his ATM card. I had two mobile phones and flitted in and out of Hindi because I didn’t speak Bengali. Of course I was muddled.

But my confusion, I came to suspect, was less the result of a divided present than a daily confrontation with the immensity of the past.

With those enormous buildings. Particularly in the late afternoon, when the angle of the sun reached through the dingy streets with a holy luminosity. When the call to prayer rose up from the masjids behind Mahatma Gandhi Road and the echo of the muezzin’s scratchy voice seemed to catch even the trucks in stillness. Like canyons and glacial grooves, in those radiant moments, the broken and unbroken windows of North Kolkata reflected back the countless sunsets to which they had sat witness. And though I was simply on my way to the metro, making my home at the end of the day, with the sound of the namaz, I stopped and looked up, entirely unsure which way was forward.

“What does time lead to?” This was a question in my daughter’s Indian Social Studies textbook in the chapter on calendars. Copying out the assignment, she paused, her pencil hesitating over the place where the answer would go. “Don’t ask me,” I said.

And yet, of course, someone was keeping track because in early April, 2019, India began its national elections, for which the voting was spread out over seven weeks, and we moved flats. After three months on the corner of two main roads where the honking kept us awake at all hours, we doubled our rent for a bright apartment on an inside lane. Immediately, the air was cleaner and the nights were quiet. We didn’t have to shout to hear one another over the traffic. But in the move, we lost what had been the best part about our first place: the washing machine, with its “daily sari” setting and the easy diligence with which it jiggled our clothes clean.

In the past, in India, I always did my laundry by hand. Generally, I liked the cold water and the wringing out of the fabric. I liked the weight of the bucket and the patience of waiting for it to fill. But now I was reluctant, especially with my daughter’s school uniform, the light yellow shirt and red pleated skirt meant to be kept spotless.

Instead, I bought more school socks and let my daughter wear her red P.E. shirt until the inside collar left a grubby mark on her neck. The heat got hotter, the soupy air left me limp, and the anxiety of the elections was just as paralyzing. Tiny, red communist flags hung along the iron terraces in our neighborhood but so did flags for the right-wing BJP, the Bengali-run Trinamool Congress, and the crotchety, yet less hateful, Indian National Congress. If paying bills at home, I didn’t know what year it was; out in the world, I understood even less what was happening. What was about to happen.

Since the Hindu nationalists had come to power five years earlier, there’d been a sharp rise in the murder of and hostility toward Muslims, Dalits, and journalists. But compared to much of the rest of the country, West Bengal remained liberal, well-educated, and passionately literary. Which was why I was looking for the legacy of Ram Mohun Moy and evidence of his empathy and dissent that I wanted to believe still existed in India. Still existed in the world. But try as I might – chatting to taxi drivers, reading the newspapers, asking colleagues at the university where I taught – no one said anything definitive or promising. Everyone made vague statements like, “We’ll see,” or offered stern warnings to stay inside on the day when Kolkata finally voted in May.

In the intersection, I clutched my kid and held by breath. In other words, twice a day, nothing mattered other than not dying.

Every morning and every afternoon, my daughter and I had to cross Prince Anwar Shah, a major, six-lane road, the traffic light for which turned red only for a few, quick seconds, one side at a time. So we crossed half the street, then waited in the middle while busses and trucks thundered past, inches from our bodies, honking as if there was anywhere else we could go. In the intersection, I clutched my kid and held by breath. In other words, twice a day, nothing mattered other than not dying.

Although I lived through the 2016 elections in the U.S., wincing as the improbable came to pass, I still craved the illusion of information. In India, without that illusion, I wondered if the opacity of the future was, in part, because getting your kid to school took so much determination. Maybe crossing the street was so dangerous that anything more was gravy. In experiencing how vulnerable humans all were, even or especially in the daily mundane, maybe I revealed the depths of my American delusion of optimism. And maybe the real reason I couldn’t keep up with the passing months was the futility of my nostalgia: that trams and typewriters didn’t mean anything was “better” after all.

Meanwhile, the dirty clothes were piling up. Under the overlapping tarps of Jodhpur Market, I inspected a bright pink bucket while a man in a worn, plaid lungi in the next stall over offered me a different bucket for half the price. But I declined; it wasn’t pink. At home, standing barefoot in the shower, I split open the packet of Surf Excel with my teeth. The water from the spigot ran hot from the tank on the roof. Soaking the P.E. uniform first, I watched the suds turn gray. The soot and grit of Kolkata traffic, of Kolkata air, emerging from my daughter’s pants.

My husband and I took turns, alternating mornings and batches of uniform socks. Crows swooped over from other rooftops when we appeared on the balcony, perching on the line as we hung things up, nipping at the clothespins. Squawking like we did something wrong.

At my daughter’s school, different uniforms were required for different days. Monday was karate. Tuesday and Friday were for the button-down shirt and skirt. Wednesday was P.E., and Thursday was when most kids had scouts, which, for girls, required its own bright blue dress and yellow neckerchief. But my daughter, who was not a Bulbul, had to wear her P.E. uniform instead.

Washing everything in the pink bucket, I had to make sure each uniform was ready beforehand. And for the first time in a long time, I knew what day it was and what day it would be tomorrow. If it was P.E. or Karate. If there were enough socks. After a few weeks, something shifted. I found my sunglasses and returned the library books. On May first, I wrote to the landlord, asking if she’d gotten the rent.

I found unexpected satisfaction in how quickly my kurtis dried.

The right-wing, Hindu nationalist BJP won India in a landslide, including multiple seats in West Bengal. The flags came down and the graffiti started to flake off. The wheat-pasted flyers for political candidates got covered up with wheat-pasted flyers for other things. The heat thickened, and the sun intensified. But on the most blistering days, I found unexpected satisfaction in how quickly my kurtis dried. How, as the belligerent crows screamed for food or attention, rather than being overwhelmed, I understood what I could manage. And keeping inventory on what needed washed or what was still on the line, I saw the entire city was alive with what was out to dry.

Squeezed in any space small or wide enough to suspend a rope, nightdresses and kurtas hung along the backs of chai stalls and across bus stops and in between guava trees. More numerous and more unifying than political party banners, saris rippled over every parapet, all six meters of orange or yellow or purple or floral print cotton, placid in the sunlight. On metal accordion gates, locked in front of doors at night, hangers dangled with undershirts and hankies. Little girls’ frocks and little boys’ shorts drooped over every blue and white divider that cut down every main street. Some cycle rickshaw drivers kept a freshly washed gamcha tied off the backseat, drying as they rode.

And those enormous old buildings were not abandoned. Pillowcases, petticoats, and more men’s undershirts hung out of windows and along twine tied between shutters.

Bed covers and inside-out men’s pants, pockets exposed, swung off cords stretched over every balcony. With the laundry segregated by gender, like the sections of the metro, there was proof of life. Of the dogged resolve to reach for the sun in the unlikeliest of places.

From the huge, dilapidated buildings up north to the vibrant, rambling houses in the south, the laundry seemed to stretch, as if on a single, zigzag line, across not only the city but also the otherwise segregated realms of class and caste. Of poverty and comfort. Of those who had so many different saris to wash and those who only had one. And when, gently, the rains arrived, the relief of each downpour was preceded by gusts of wind and tumbling storm clouds and the rush—onto rooftops, through open windows, along railings—to gather up the laundry. To protect what we could.

In a city of so many millions of people, I had lost the ability to see any one person. To keep track of even myself or the hour. But at every sari unfurled over every veranda, the tenderness of humanity reasserted itself. Ragged towels and frayed gamchas, blue jeans and blue lungis; clothes on the line were personal, private, even intimate. As human as the people waiting to inhabit them.

And now I knew. What does time lead to? It leads to next load the laundry. Returning to the quotidian wasn’t a retreat from the larger abuses of power, from corrupted elections and injustice, but rather an embrace of everything worth protecting. Confirmation that while we are all indeed vulnerable in our daily mundane, the camaraderie is also edifying. This need as basic as food and shelter to take what is dirty and make it clean.

“Look!” my daughter said the other morning, from the lane in front of our building, while she smirked and pointed up. “I see Papa’s underwear!”

It was true; through the white grille that enclosed our little 4th story balcony, a row of my husband’s boxers fluttered on the bungee. The silhouettes of our existence joining the contours of the city. This brief evidence, amidst the immeasurable history and the immeasurable present, that we were here, ready, with clean underwear, for tomorrow.

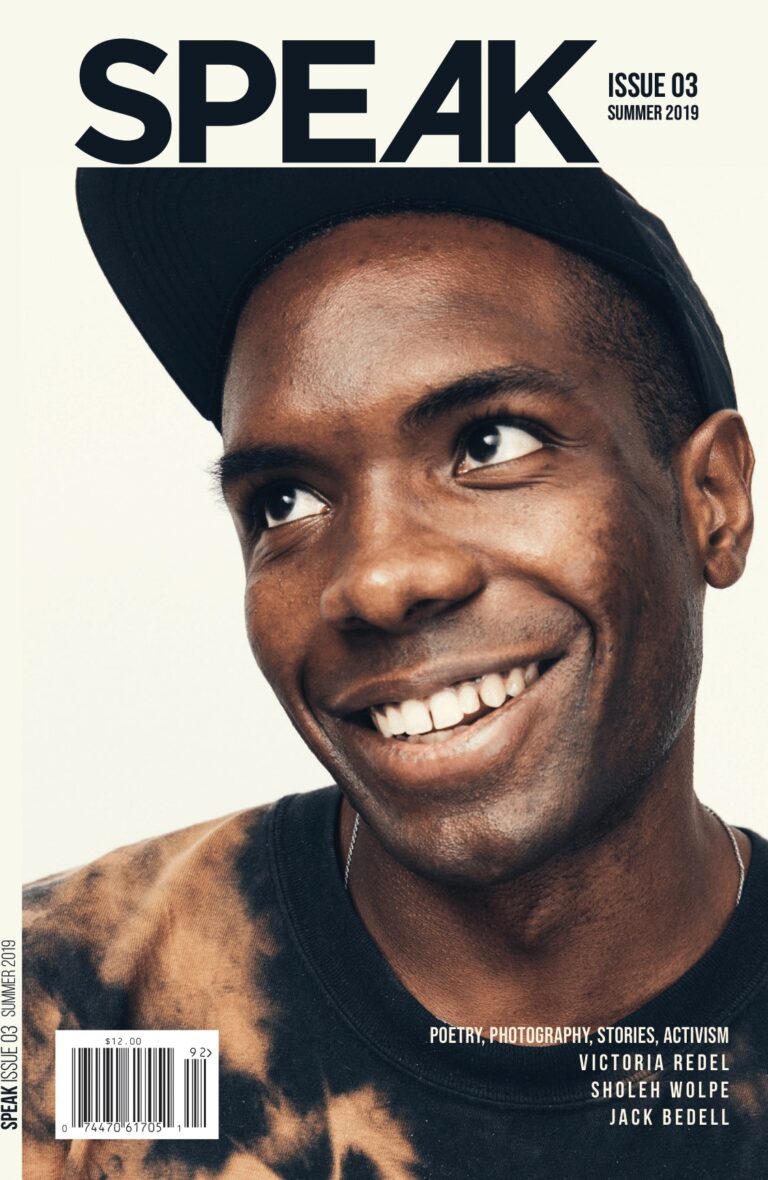

meet the author

Liesl Schwabe

Liesl Schwabe’s essays have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Words Without Borders, Creative Nonfiction, and The Rumpus, among other anthologies and publications. She served as a 2018-19 Fulbright-Nehru Scholar in [...]

Read More

Subscribe to our newsletter