A few months before, a strange set of circumstances had conspired to turn me into an Indian poster girl. That image Chien Wein Lee had taken of me in a risque red swimsuit was released on the cover of Gladrags in India in August 1991. Indian fans are notorious for their ability to fall in love at first sight. Overnight I became an object of adulation, a cover girl for an India that was opening up to new possibilities. Once the fans seized on my Gladrags pictures, I was in demand. Later, I heard stories of billboards that caused traffic accidents on Marine Drive. Directors and producers who managed to reach my father or me were salivating, offering Bollywood films and modelling contracts.

Yet this was no consolation to me. Back in Toronto, it was touch and go with my mom. We didn’t know if she would make it at all. After a few weeks, her condition finally stabilized and she was transferred out of the ICU, wearing a halo ring, a contraption like a crown drilled into the skull. All the while I stood silently by the curtain divider in her room. Doctors bent their heads to whisper to my father and me. Their words admitted nothing, a professionally veiled language that made me feel even more confused. I felt stranded in those hospital rooms. Helpless. Standing on the edge of everything. Trapped in blankness. Push it down. Stay strong. Manage!

In that moment I splintered. Some part of me was left behind there by the side of the highway

A large percentage of people who suffer from spinal cord injuries are very active before their accidents and get hurt in the course of a daring activity, like skiing or diving. In her own way, my mother was one of these people. She was vital and restless, the kind of woman who would never stay in one place for long. She used to roll her eyes at my dad and me when we curled up on the sofa. She would rarely sit through an entire movie. “Sitting? How about doing? There’s tomato sauce to be made. Come, help me peel the beets. I’m going to bring the laundry in.” To see that energy stilled was a huge devastation. Little by little I found temporary relief in the repetition of waking, hospital, dinner, and I focused instead on helping my dad with paperwork required by the lawyers and insurance agents who spoke in low, pacifying voices. I remember my father’s mannered, elegant handwriting filling form after form. It was a tort case because the driver responsible for the accident had fled the scene. I’m not even sure he knows what happened.

Something else happened at the site of the accident which was never spoken about. I had a moment of hyper awareness—the realization that the car was going to hit us, a blunt and obvious “Oh, really? Now?” And I was strangely detached from it. In that moment I splintered. Some part of me was left behind there by the side of the highway, while the other part needed to outrun everything, all the fierce attachments that caused me pain. I hadn’t yet figured out that a life in pieces is grace; you can put it back together the way you want. That understanding would come much, much later.

Once the initial crisis was over, my mother began the long painful road of healing. The good news was that she was going to make it, the bad news was that she would not be able to walk. Soon we moved from trying to accept the idea of her life as a paraplegic—the initial diagnosis—to one as a quadriplegic. My father and I were exhausted, and when the calls from India came in at night, I would get panicky, hanging up quickly. Then one night the phone rang and it was Maureen. She had tracked me down, but she still didn’t know about the accident. I told her, the words feeling bulky in my mouth. She answered back, clear and certain. About a week later, she flew to Toronto.

We didn’t have any family in Toronto to call on in this crisis. The three of us were leaning on each other, but it was a lonely time. My parents, it seemed, had the pilgrim spirit in them. Since leaving their families they had become entirely self-reliant and not used to asking for help.

I too have always found it difficult to ask for any kind of support, so it meant the world to me that Maureen came all that distance, showing up at the hospital. Our lives had come undone and in came Maureen, in control, unflappable and managing every situation. Even the doctors seemed both fascinated and cowed by her. She sat on the edge of my mother’s bed with perfect flourish and established an immediate intimacy with both my mother and father. In contrast to the stark, intimidating certainty of the doctors was Maureen, adorned with a different sort of certainty— characterized by her expensive pastel suit and sloe-eyed affluence—that somehow or other, things would work out. Watching this play out in the starchy white setting melted something inside me. I was grateful to her. It was simple; in a moment like that, you are deeply grateful for any kindness. I remember Maureen stretching across worn hospital sheets to hold my mother’s hand. She had a proposal. I was standing in the doorway, a part of me holding back, watching what felt like a scene from someone else’s life. I heard her say in her modulated English to my father, “Send Lisa back to India. I’ll look after her.”

Of course Maureen had broached the topic with me. Would I come back to India? It was an opportunity to extract myself from the tableau at my mother’s bedside. Now that my mother was to be transferred to a rehabilitation hospital there was even less for me to do. In Bombay I could wring myself out and find my feet again. Oh, and of course, I could stay busy modelling for Gladrags and Bombay Dyeing.

All this while, my mom was heavily medicated. Speaking through the drugs, she would murmur: “I don’t want to live like this.” She was forty-nine years old at the time of the accident. But somehow, in a remarkably short period, she called on her tremendous will power and as the drugs eased, she stopped saying that she wanted to die. Looking back, I’m convinced that she faced her illness with ironclad resilience primarily for my father and me—for the ones left standing.

Eventually, she was ready for the transition from the hospital to a rehabilitation centre called Lyndhurst. The hospital season was passing, but now we knew it would be months of therapy before she retrained her body and learned to live in the world again.

I imagined exploring this little chunk of time in India, avoiding the snow and the heartache at home.

In this atmosphere, Maureen’s offer wasn’t a business proposition but something entirely more personal. “Give Lisa a break from all this,” she told my father. She promised to be my guardian, to keep me occupied with a few months” work, and then send me back to Toronto. I knew that in Maureen’s company, I would get all-encompassing hospitality. Maybe on the other side of the world I could out-smother the highway, the sound of the gravel and the desire to see my mother made whole again. And to be honest, I wanted to get the hell out of Toronto. By October I had healed physically, and the neck brace was gone, but my mind was heavy and sluggish. I could feel winter approaching in the air and the shorter, darker, depressing days. For the first time in my life I didn’t really have a plan. I imagined exploring this little chunk of time in India, avoiding the snow and the heartache at home. I could return to university later. I pretended it was a gap year. Some kids go to the tourist area of Haliburton County and work in a kids’ camp, others go backpacking and volunteering though South America. I would go to Bombay. (I deferred from university so many times in the subsequent years that I had a thick stack of letters from them. They finally gave up on me.)

There were no heart-to-heart chats with my mother during that time. The truth was she was preoccupied with trying to understand her new life, as far as it would be susceptible to understanding. But my dad, with typical generosity, told me to go. “You need to get away. Don’t worry about anything here.” I was almost seventeen. I see now that I was running away from something than running towards something. It was an ironic kind of serendipity that drove me, the daughter of immigrants, back to India.

But the birth of my success is forever linked in my mind to the accident. You might say my career in India began on the edge of sword: fame on one side and on the other, grief. My mother would never have the use of her legs again. From that 1991 crash until her death in 2008, she would live her life in a wheelchair. And throughout those years, I would keep flying away.

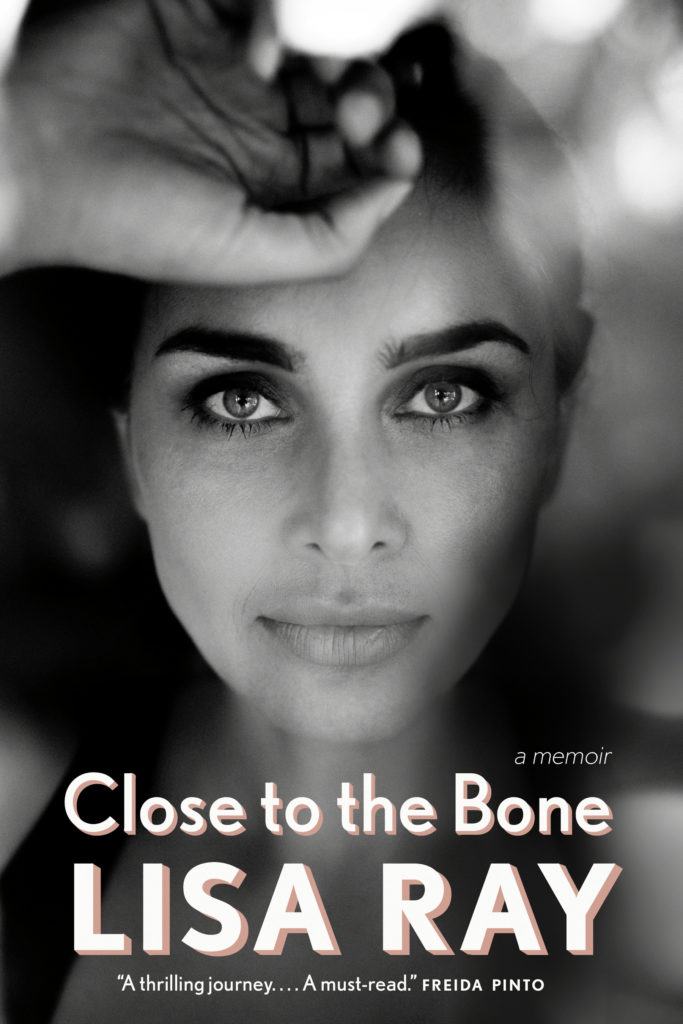

Excerpted from Close to the Bone: A Memoir by Lisa Ray. Copyright ©️ 2020 Lisa Ray. Published by Doubleday Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

meet the author

Lisa Ray

Born of a Bengali father and Polish mother in Toronto, Lisa Ray has had an acclaimed, expansive, and serendipitous career in the entertainment arts beginning in India in 1991 and spanning multiple countries and including film (Oscar nominated Water), television (Top Chef Canada), and modeling (video [...]

Subscribe to our newsletter