I am getting desperate.

In the far corner of my study, behind my wife and son, high on a bookshelf atop a pile of American novels, lies a clear, dusty, plastic bag closed with Scotch tape. I can see it from where I sit before the blank screen of my computer.

“Write about how you walk her every night and she loves it,” Doris says.

“She’s such a bad dog,” adds Kevin, smiling. “She doesn’t deserve a walk.”

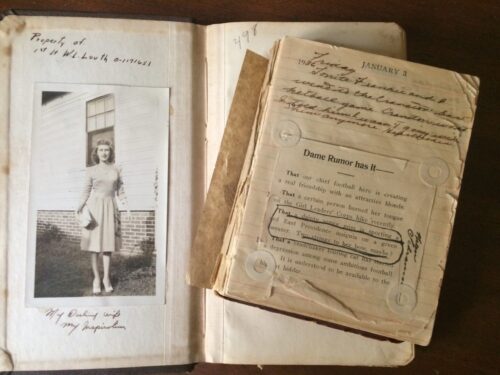

In the plastic bag are two small journals: a brown leather Transit Book that logs my father’s final flights during World War II in the winter of 1945 and my mother’s diary from 1936, the year she graduated from high school and started college.

They tell me I can write about my dog.

It is that lazy time, just before dinner. The dog does not move, does not acknowledge that we are talking about her. She lies across her sofa, white with a black Mickey Mouse spot on her side, other black spots scattered like buckshot around it. Her eyes are closed. She pretends to sleep. On the back of her lids, a silent movie plays. In it, two laughing boys on bikes lean over her, where she lies in a roadside ditch, and shoot her with pain and paint. Air grows cold about her. A shadow appears; strange arms cradle her, and as she’s lifted high into the air, she hears the savior’s voice say, “Good girl.”

Friday, January 3, 1936

Tonite Frankie and I went to the Cranston baseball game. Cranston won. I told him I wasn’t going with him anymore. Heartbroken.

I’ve gotten in the habit of walking her every night when I come home, after I’ve had a beer. As soon as I move towards the kitchen drawer where her maroon leash is kept, she becomes alert. All I have to do is say, “OK,” and she erupts, leaping to the door and turning in circles, barking, growling, the same high-pitched sounds from deep inside each time as I lasso her with the leash and pull it tight around her neck. “You are such a bad dog,” I say while she sniffs at my leg as if she will bite it off, then growls at the door as if it is an animate thing.

Wednesday, February 21, 1936

Oh, Guess what! Boy Clifford asked me to go to the Hi-Y dance with him Friday. Swell. Turned down dancing date with Frankie. . . .

Since it is night, the dog does not look out the window in the study. Each morning I leave the curtains open for her and secure the curtain strings on a metal hook so that she will not strangle herself in a fit of barking if a neighbor walks by.

Tuesday, March 2, 1936

Went down city today with Barbara. Met Roy Johnson on way home. He asked me if I was going to the Hi-Y. He was going to ask me, but Bill—Bill—Bill. . . .

She lies, breathing softly when we refer to her, listening for her name. At night, there is only the sweet, deep, soft safety of her sofa, its warm familiar lumps and holes, its purple car mat surface, its soggy old pillows. She has done her job for the day, to rise at seven when she hears the alarm clock upstairs, to bark, to pee, to stare out the window for walkers, to trot from kitchen to study with each passage of a family member.

Wednesday, April 1, 1936

Finished with Bill. After school Bobbie took me home. Then we played baseball in front of the house.

“I must write tonight,” I say. “I will have to write all night. It is due tomorrow. If I had not put it off, well. . . .”

My wife and son try to help in their own way while the dog listens.

“What of the Van Gogh?” Doris says, pointing to a small picture of his bedroom that hangs above me. His bed sails like a large brown ship before a cracked window in his blue room while two cane chairs with green cushions stand at attention in the corners of a worn and tilted wooden floor. Van Gogh’s portrait and that of a woman lean menacingly over his bed. His room is claustrophobic yet alive.

Below it is a photo of my parents before the war, above it, a picture of me receiving an award at the Governor’s Mansion, my wife at my side. My stance is identical to my father’s sixty years before, and in both, the women smile the same. I look at my mother and try to imagine what she is thinking as she looks into the camera.

Friday, May 1, 1936

Date with P. Kingsley tonite. He’s nice. I like him. We went to the Loews State Theatre and then to Albert’s. Fun. I’ve got another date with him for Sunday. He kisses neat. Oh.

“I can’t do this without a pizza,” I say, expecting argument. “This can’t be done without a pizza,” I repeat. “And you can use my taped one dollar bill as a tip.”

“What would you want on it?” asks Doris. I am surprised. We have never ordered pizza together before that I can remember. Kevin is smiling ear to ear at the novelty.

“Onions and peppers,” I say. It is the first thing I have said to her with conviction since January. Doris and Kevin disappear into the kitchen; then I hear them talking of coupons. Domino’s has one kind of special, Papa John’s another. Doris returns. "You could have two toppings and a second pizza,” she says.

“Fine,” I say. They have already gotten me to admit that, given a third topping, I would take mushrooms. But a third topping would not be a special, and we must have a special. “Onions and peppers?” she asks. “Yes,” I say, feeling that it no longer matters. I’m not really hungry, just empty.

Thursday, July 9, 1936

Went swimming at Gordon’s Pond. Went out boat riding with the lifeguard, and he tried to neck with me.

Six months ago I had a 34 inch waist, but tonight when they were cleaning I tried on a pair of my older son’s 32 inch jeans, and they fit me fine. They fit and felt good. I don’t care about food. All I care about is writing and sleeping. I want someone to write this for me, whatever it is, and then sleep. I want someone to write this for me while I sleep.

Friday, July 10, 1936

Today I met Glen Smith, a jockey from Detroit. He took me swimming in his big yellow De Soto. Gee, he’s smooth and he talks like a Southerner. He likes me and does he kiss nice. I’m—Uh Well! He wanted me to go moonlight swimming. But I demurred. Went out with Mac to the Hollywood. Saw Bill Cashman and George Naillcard.

“Well,” my wife says, “there are the pictures on the wall. There is the picture of the family for Christmas 1997 that you drew on the computer.” She looks at me. No response. She does not understand. It is not easy as letting the dog out. It is not easy as going to the mall. It is not as easy as going to church. It is not easy.

Monday, August 3, 1936

Well, Carroll + Stooge came over tonite. We just hung around the house but had lots of fun. Carroll looked like a dream. He had white flannels and plaid shirt on. Cute.

“Or the picture of your parents,” she says. Again I look at their photo behind me, directly above the cans of pens and pencils. It is a photo from the 1940’s, probably 1942. It was taken in black and white and tinted later by the photographer, giving it a strange and dreamy air.

Monday, October 26, 1936

Well today was my birthday. 18 years old—one foot in the ground and the other slipping.

My parents stand beside each other in 1942, my mother’s left hand under my father’s right arm. His hand is in his pocket, and he looks relaxed, though their outfits are formal. She wears a long lime green dress, only the skirt showing, with a furry white waist-length jacket, a huge corsage of flowers and a pink bow on her right shoulder, matching a pink bow in her hair, and pink cheeks. She smiles gently.

Tuesday, October 27, 1936

Today we got out of school to see President Roosevelt at the statehouse. I saw him right close to me.

But my father’s face is in shadow. It is a few months before he will leave for the war. He wears a deep green military jacket with artillery crosses on both lapels, shiny buttons, a thick leather Sam Browne belt, and the sturdy pink pants that I later found hanging in the attic and wore on cold mornings in college. His left-hand hangs loose, but his right hand, cradling my mother’s arm, holds the button that snaps the photo. The cable to the camera runs hidden down his pants leg. Like his face in shadow, there is mystery to the photo. On his chest, there are no wings yet. He is not yet what he will become. He will have to earn his wings.

Monday, November 2, 1936

After school today I went to the Junior party. There was a swell orchestra. At night went out riding with Larry and Lenny. Got in about 11:30.

I pet the dog behind the ears, then get up and move the hassock underneath the corner bookshelf so that I can reach up, but my arm is not long enough, and I can only touch the rough yellow edges of the unread novels below the plastic bag. In the kitchen I hear Doris call in the pizza order, negotiating it over the phone. I can tell she is even more excited than I am.

Thursday, November 19, 1936

Today I bought the tickets for the dance. At night saw Andy. We fooled around and then-

My left foot balanced on the hassock, I raise my right foot to the armrest on the black swivel chair, the very chair my father used to sit in telling me his stories, and with one thrust I am standing on the edge, one-footed, rocking, balanced, the plastic bag in my hand.

Thursday, November 26, 1936

Today is Thanksgiving Day. Went to LaSalle+East Providence football game with Frankie Burdick. Went over to his house for turkey dinner. Then at nite Barbara and I and Jared + Frankie. When I got home I found out that Carroll Palmer had been over; I could have broke my leg. Frank Docekral + Lenny also came over. But I couldn’t leave him, even though he bored me to death.

“We’ve ordered from Domino’s,” my wife says as I return to my desk with the plastic bag and she enters the study. Moments later a car with a lit Domino’s sign passes our house, backs up, and nudges into the driveway. It is too easy. I watch Kevin stroll up the driveway with two boxes in his hands, and the car backs up and goes away. The dog pays no attention. She is able to smell him approaching, even through the walls, and hears him kick the gravel.

Friday, November 27, 1936

Well today I went to the show. Carroll came over looking for me + he came to the show and found me. He’s looking neat. Gee! I like him. We went out together and oh—what fun— Earl called me.

I open the plastic bag, slide out the two journals and a single sheet of paper on top dated June 6, 1978. Pushing that paper aside, I flip open my father’s log book and read the first page of his writing.

January 1, 1945

Started off 1945 with a bang. Went up on a patrol with Dick Dunn my observer at about 0845, started to reconnoiter area south of our sector looking for Jerry vehicles and troops; we climbed to 4500 feet to keep away from Jerry small arms fire. We were sailing along up there when we got a flash warning, ME 109’s in the area. I got down from there in a hurry, looking at my airspeed saw we were doing 170 mph, "Pretty good for a Cub,” wings didn’t shake much either. We then flew around close to the ground waiting for Jerry to leave the area. We started to climb back and continue patrol, noticed an M.E. come up under another L-4, he missed him and the Cub peeled off and headed straight down. The M.E tried the same thing, he was about 800 feet, he must have stood on the rudder because the M.E. whipped over and went straight down. I knew he would never come out of that, he disappeared behind a small hill and a burst of black smoke floated up, over the hill floated the little L-4, an M.E. 109 to his credit, he earned it. Just then two more M.E’s started for us, I got right down on the ground, while Dick gave me a running account of where the M.E’s were, we took violent evasive action weaving and turning, stood the ship on its side to go between two trees, clipped a wire with my wing tip . . . ack ack firing drove the M.E’s off, we continued on to our field landed very hot and jumped out ready to run like hell, the M.E’s left us alone and looked for easier pickings, I’m glad to see the end of this day.

I close his log and grab the lone piece of paper where I had copied my mother’s last words to me shortly before her death. She had been lying on the flowered sofa where she used to read her novels, with a wet washcloth on her forehead, and I did not know that she was dying when she spoke. “You were always the strange one,” she said. “Your father’s a brilliant man, but he can’t run a house. You must have got your brains from your father, your dreams from me.”

I close my eyes. Talk to me, I am thinking. Talk to me. I lay my hand upon her journal, and little shavings of dried brown leather flake to the desktop. I do not even know what I am looking for, so how can I find it?

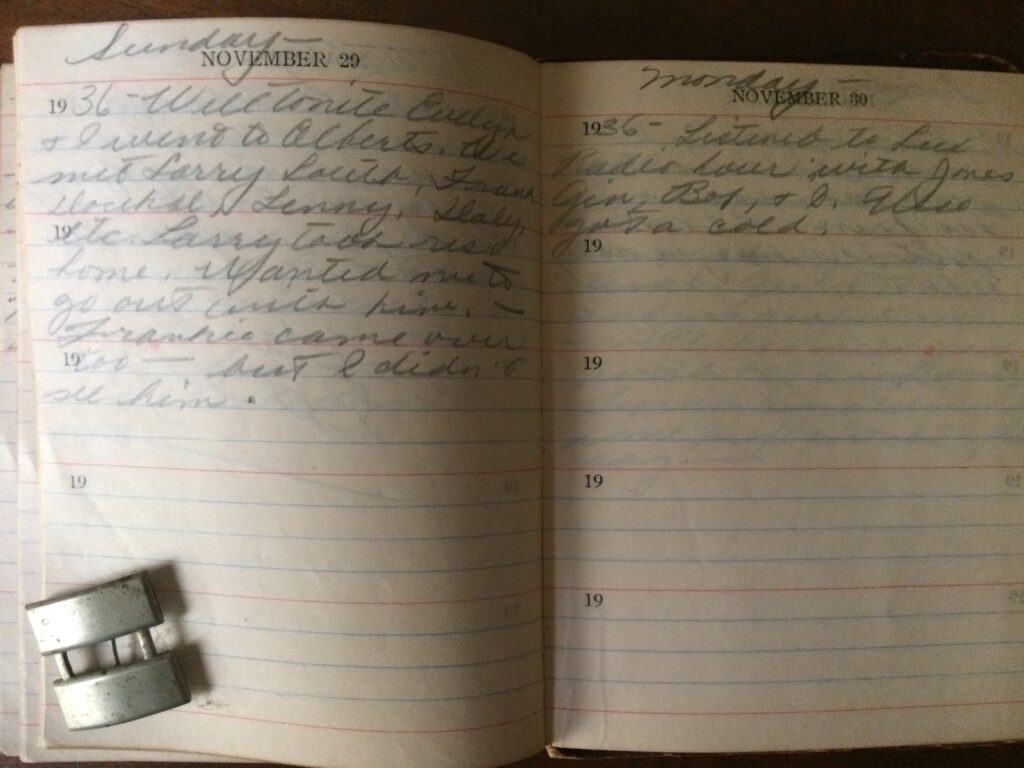

Sunday, November 29, 1936

Well tonite Evelyn and I went to Alberts. We met Larry Louth. Frank Docekral, Lenny, Daly, etc. Larry took us home. Wanted me to go out with him—Frankie came over too—but I didn’t see him.

It is there. Before me, in her own hand, her first recognition of my father. Just another boy who wanted to go out with her. I look for him elsewhere in her journal, but he’s not there.

I look at my father’s black swivel chair, which is now in my study. It has stopped rocking. When I was a child, my father told me war stories almost every night while my mother read pulp novels on the flowered sofa smoking Salem menthols. The one about how he turned his plane on its side and flew between trees was a favorite. Or how he painted a captured Jerry plane olive drab on the last day of the war and flew every villager in it. But the story of how he earned his wings came later, much later, one of the final stories when he was drunk and dying and sitting on the living room floor. It comes to me now.

It is about two moments missing from the journals and the photo of my parents but connected to them and to me in some secret way.

The first moment occurred near the end of his final test flight as a young second lieutenant, high in the blue skies of Alabama when my father did not see the flight instructor reach over his right shoulder to shut off the engine, stalling the plane. The plane banked violently to the left and flipped, throwing my father against his door, bursting it open, breaking his seatbelt, and almost ejecting him from the plane. He grabbed the stick between his legs to keep from falling out, then nosed the plane into a dive, caught the wind under its wings, and prevented a crash. “You’re washed out,” the instructor said. “You grabbed the stick.”

“You sonofabitch,” my father replied. “You can’t kill the engine during a test! My seatbelt broke. I would've fallen out. We’d’ve been killed. I had to grab the stick!”

“You grabbed the stick in a stall, so you’re washed out,” said the instructor. When they landed, they went to the C.O. at my father’s insistence, and the C.O., who knew that instructor’s reputation, determined that my father should have another test. He passed it with ease.

The second moment occurred over a year later when, as a squadron commander in France, my father watched an L-4 circle his field and land. The pilot stepped out, walked up to my father in the dying light, saluted, and said, “Permission to land in your field, sir.”

My father looked at his face. “Permission denied.”

The man repeated, “Permission to land in your field, sir. It’s getting dark; Jerry is all around; there is no other field.”

My father replied, “Permission denied,” then unholstered his 45 caliber pistol, pointed it at the pilot’s head, and said, “Get your god-dammed plane off my field or I’ll blow your head off, you sonofabitch.” Their eyes met. “Remember me? I’m the guy you tried to wash out.” He pressed the barrel to the man’s skull, and the man looked at him one last time before climbing back into his plane and disappearing into the night, never to be seen again. By anyone.

“Come have some pizza!” shouts my wife from the kitchen. The dog rises.

I take one last look at the picture of my parents, the bright light on her white fur jacket, the shadow over his face, and tuck her journal and his log back in the bed of the plastic bag, one on top of the other, with my torn piece of paper on top like a sheet. I feel as if they are speaking to me, and that whatever it is they whisper across the pages and the years, I must put it down in words for my own child. I will leave this that I write today for my own son to find and figure out, along with my parents’ journals. He will find it at the right time, I hope, and he will see his part in it, too, and will pass the story on, adding what he must, just as I have.

My son enters my study chewing on a piece of pizza with Canadian ham and mushrooms. “It’s good,” he says.

“Good,” I reply and rise.

With pizza in my belly, my piece written, my parents’ journals back in their spot atop the bookshelf, I am finally able to sleep. I dream that I am back in Cranston, Rhode Island, in the home where my parents raised me, down the street from my grandparents' house where my mother recorded her high school life and my father snapped their photograph. It is the home she bought him when he returned from the war. I am in my old bedroom, morning light beams through my window, and I am looking up at my wife, who straddles me in a lace nightie. She is younger, and so am I, and we laugh and talk as I feel the lace around her neck with one hand and run the other around the crescent of her inner thighs. From outside the window comes a mechanical, disturbing noise.

“I didn't want to tell you,” she says, “but they are working next door.”

I look out the window to view an enormous machine cutting the grass of my neighbor's lawn and straying onto the thin border of our property as well. Then I find myself outside, riding a bicycle along the edge of our property, flying towards the back yard. The machine is gone, and all our grass has been trimmed. I turn, fly back past the window of my bedroom towards the front of our house, with the grass growing taller and taller as I pass the window, so tall that I feel its seedheads brushing my calves as I peddle through.

At the corner of the front yard, I stop. It no longer looks the same. Now a neat garden fills the yard, and I recognize the plants and remember planting them once. In the far corner of the garden by a small tree, I hear a rustling and glimpse the form of something moving through the tall grass towards me. When it emerges, I recognize it as an old German Shepherd named Mr. B, or simply “B,” that our family raised from birth in Louisiana. But he had died when the children were still young, put to sleep in the vet's parking lot when he could no longer walk.

We had buried him in a garden patch where Sophie, our only remaining dog, runs every evening when I come home. What is he doing in Rhode Island, I wonder, and how can he walk if he is dead? In my dream, Mr. B moves forward on wobbly legs, an area visibly decaying on his large nose. He comes to me, and I put out my hand to pet him, and I say his name. As I pet him, my son Kevin walks up from behind, much younger than he is now.

“Do you see him, Kevin?” I ask, for I know that “B” is dead, and I think he may only be visible to me.

“Yes,” he says, and pets him, too.

“Go inside and tell your mother to come right out,” I say, thinking the dog will disappear, and that she will never believe me. I want her to be part of this. So he goes up a set of stairs and emerges with my wife, who says in recognition, “Mr. B!” It is one of the most beautiful and real moments of my life, though just a dream.

meet the author

Richard Louth

Richard Louth is a Professor of English at Southeastern Louisiana University, where he has taught for 42 years, and is founding Director of the Southeastern Louisiana Writing Project. Louth received his B.A. from Brown University, where he studied under R.V. [...]

Read More

Subscribe to our newsletter