- The Call Came

The Call Came to my cellphone at 4:00 in the morning. I was sitting downstairs in the living room. Which is very unusual. Though I have difficulty sleeping, I almost never leave the bed. But this night, for whatever reason, I did. I did not have any foreboding about anything, I just happened to be wide awake.

I remember years ago when my father’s mother died, far away in Riga, my father claimed that he had stayed up all night in a state he described as the calmest wakefulness—this before getting the news.

I was downstairs just sitting in my armchair. I don’t know what I was doing or thinking, when my phone vibrated. As soon as I saw the caller ID on my screen, I knew. Nothing mysterious there, it’s common sense—it was the logical deduction. The hospice nurse told me that the attendant had called her and that she had just checked for heartbeat and breathing—

And my father was gone. The nurse said that it had happened quietly, that the attendant had made a routine check and found that he was no longer breathing. There had been no struggle, no noise. My mother was still sleeping right there in the next bed. I said they should let her sleep. I would call my sister and we would tell her together.

- Gone

If anything is strange, it’s this. You live your whole life imagining how it will be, and then it is, and it’s not like you imagined. I wonder if it ever is.

What you don’t ever imagine, I think, is the lag. You imagine a certain person dying and then you imagine your reaction happening then and there based on your whole life with the person. You can’t imagine that at first there will be nothing, no jolt, no sense of an abyss opening, no inrush of sorrow.

I speak just for myself here.

As soon as I hung up with the nurse I called my sister, who answered promptly, though it was not yet 5 a.m. She was unsurprised and matter of fact, as was I. There was no remarking the enormity of the news. We agreed to meet at the apartment in a half hour and then tell my mother when we were all together, and wait for the people from the funeral home where he would be taken for cremation. This contact had been arranged beforehand with the hospice people—they required it. His wishes were known. He wanted to be cremated and then kept with my mother until she should die, at which point they would both be buried in Latvia at his family’s gravesite. The space for the urns had already been prepared.

- I Don't Remember Much About Driving Over

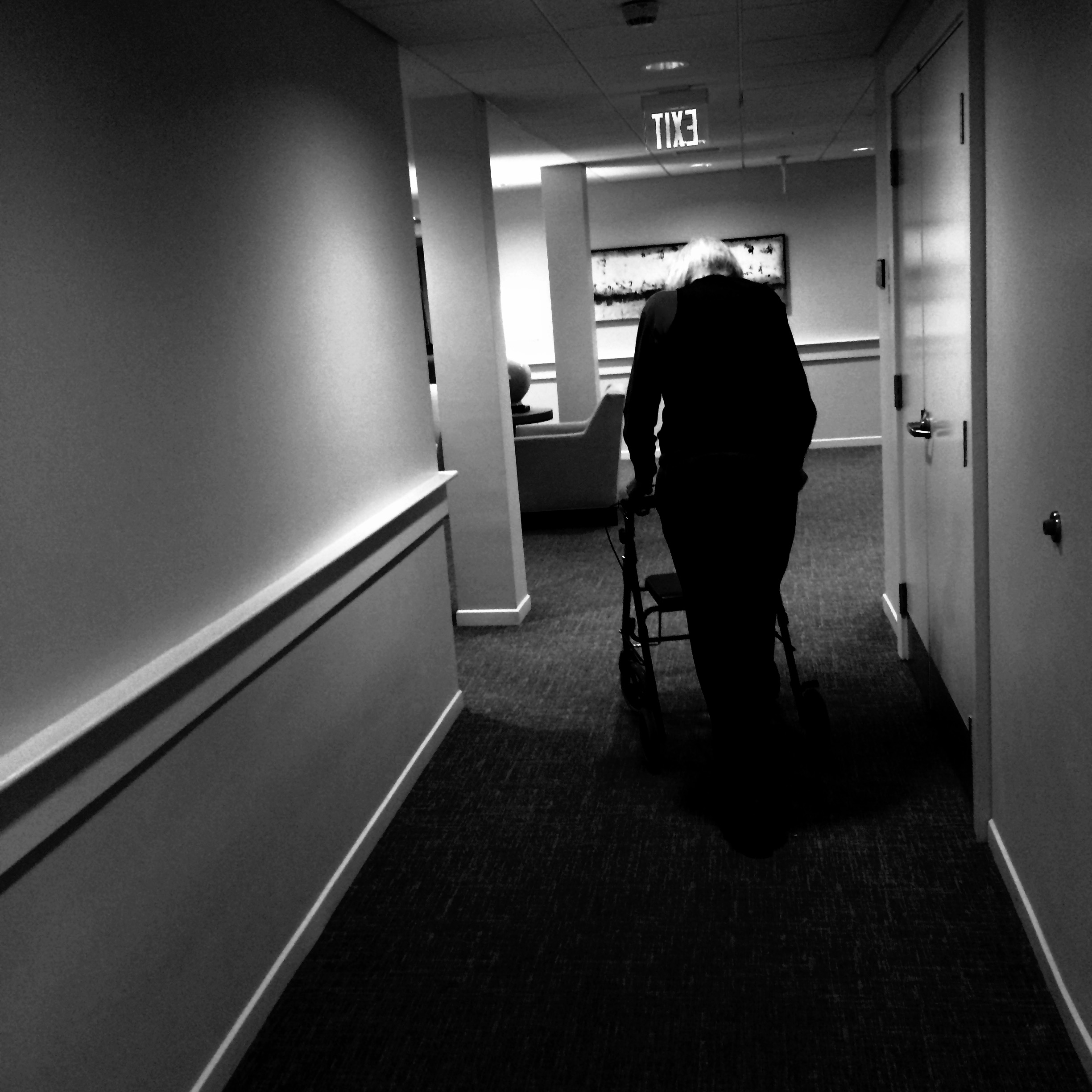

It was still dark and I drove in silence, no radio. My focus was less on the fact that my father—the towering figure in my life—was gone, and more on what I would find when I got to the residence, whether my mother would still be asleep, how we would tell her and how she would react. My sister and I had agreed in that early call that after we had told my mother, she would take her to her house, and I would wait at the apartment for the people from the funeral home.

Everything happened as in a dream one has dreamed before. I got there before my sister did. The door was slightly open and a nurse and an attendant were inside. They were sitting quietly at the table in the main room. We acknowledged each other without speaking. I stopped in the bedroom door and right away took in both shapes—my father’s on the raised bed just inside the door and my mother’s in her bed across the room.

Without thinking, I stepped closer to the hospital bed and looked. Maybe I was braced for a shock, I don’t know. But I had no immediate response . That he was gone was still a thought. Just then, in the dim light coming from the other room, he looked much as he often had when I walked into his room at rehab and found him asleep. His mouth was open, the skin sagging away giving his nose a sharper look. I won’t say I expected him to open his eyes at any moment. I didn’t. But I also did not feel any crashing sense of sudden absence.

The dark outside went on and on. My sister arrived. After giving whispered condolences, the nurse and attendant receded as far as the big room would allow. I remember I signed a few papers. We conferred about the arrival of the people from the funeral parlor. My sister went into the bedroom and I heard her quietly waking my mother.

There was no drama. I don’t know what I expected. There was very little reaction of any kind. My mother let herself be helped into her clothes, and seemed dazed when my sister led her out of the room. I don’t remember a goodbye moment. Did she stop at the bed and touch his hand? I had not touched his hand yet either.

I told my mother and sister that I would call later. The nurse and attendant packed up, once more gave condolences and left. I was alone in the apartment now, waiting for the men to arrive.

- The Ring

I was there maybe a half hour. I walked slowly back and forth in the two rooms, I couldn’t sit. Not long after my sister and mother had left, my sister texted me to say I should remove my father’s wedding ring.

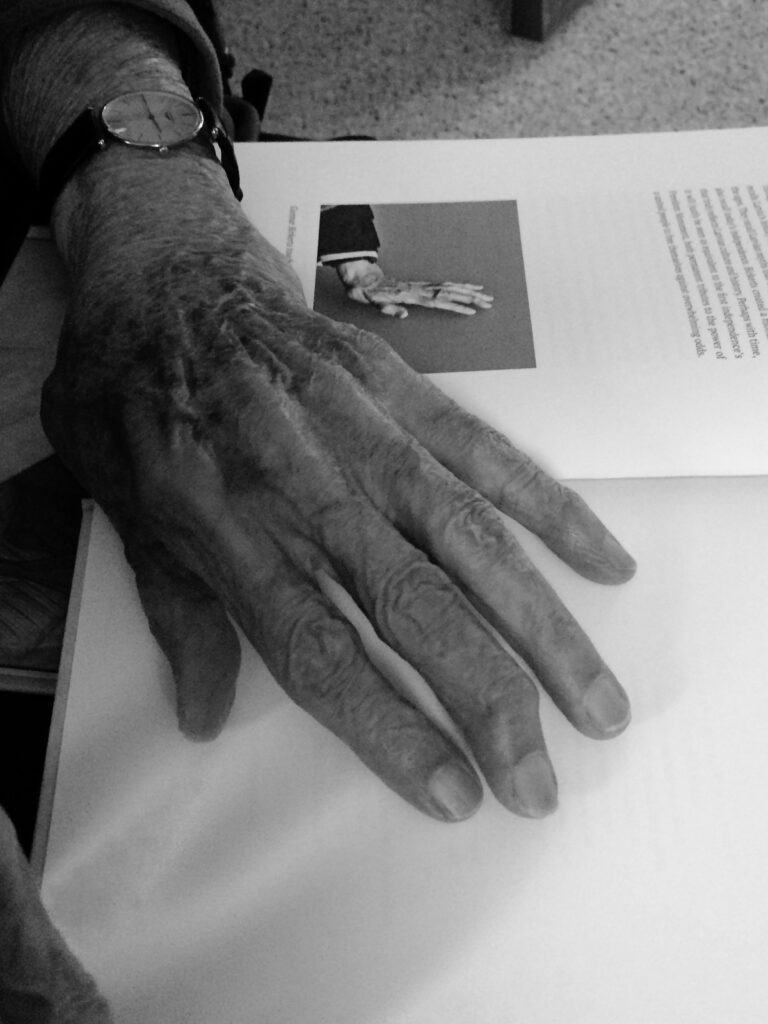

That was the first contact, I think. It was purposeful, not sentimental. I saw the ring there—his hands had been folded across his chest—and I knew I should try to remove it right away. Again, no preambles. I reached down, registered the cool and stiffened flesh. I was sixty-five and this was the first time I had touched a dead body. I tried to twist and pull the ring toward me but it would not come past the knuckle. Setting the hand back, I went into the bathroom and soaped my left hand. I returned and tried again. Still no luck.

At that moment I heard the light clattering sound out in the hall. I opened the door to find two expertly deferential men in dark clothing. One of them was pulling a gurney. The other nodded gravely and offered condolence at our loss.

They rolled the gurney into the bedroom doorway and got ready to transfer the body. Before they moved to lift, I mentioned the ring. The man at the head of the bed took one step, bent over. I heard the faintest sound, as of a knuckle cracking. A single movement and he handed me the ring, which I promptly wrapped in several pieces of tissue paper and put deep in my front pocket, under my wallet.

- The Family Memorial

When we organized the family memorial back in October—so recent, really—we set up a big screen in the church so we could show a 20-minute film that a Latvian group had made in the last few years of my father’s life. They sent a link when the death was announced, and I previewed it on my laptop. There were shots taken here in Massachusetts when the crew came to shoot, and others taken in Latvia, from several late visits he made, including the visit to commemorate the opening of the library in which he had a starring role in the ceremonies.

Watching the video on the small screen—I was propped up in bed at night—it was not overwhelming. In truth, I was not watching in an immersed way, but sampling, looking to see if this was a film we could show at the memorial. And I thought it was. At that moment it did not affect me nearly as much as when I sometimes found clips from lectures he’d given in years past, when the whole look was different—hair, glasses, clothing, and of course the fact of his youth itself. But this is hardly particular to him—any such confrontation of recent and former can deliver this shock.

I was mainly screening on behalf of my father’s grandchildren, to see whether the film presented a man they might remember, their “Opa.” And there he was, seated in his studio, walking along in front of the Boston Public Library, at the ceremony in Riga (which they had all attended). When we were all gathered at the church, my son cued the film up from my laptop.

And there he was, indeed. The lights were down and we were looking at the big screen. I had not accounted for the difference.

“Big as life—” that’s the idiom. Or: bigger than life. It was a jolt for me, sitting in a room with people who had not seen the film, and who mostly had not seen the man in a long time—seven grandchildren altogether—to have him rear up in full distinctive voice and manner.

Gunnar leaning back in his desk chair, pontificating—that was the most familiar set of clips—but there were others, some surprising, to me at least. In one filmed sequence, he is walking the street near Copley Square, a place I never fancied him walking. He is using his cane and has that particular jerky walk he had before the bigger decline set in, the one that put him mainly on a walker. He looks at once dapper and injured. In another, he is in Riga, standing by the family gravesite, clearly contemplating last things (which he had carefully arranged a long time in advance—the construction of two slots for urns (his, my mother’s), and sliding stone panels to cover them. I know that cemetery. Pretty much everyone in that room knew it, for we had all gone there as part of a day-trip on the occasion of the visit for the library ceremony. I have always thought of it as a kind of home place, ever since my first visit in my teens. The meandering paths, the shade, the stones, the spacing of the stones…

Many things about the film were affecting. As it was narrated in Latvian and most of the people in the room (spouses, grandchildren) did not speak the language, I felt it my job to jump in with explanatory bursts. “Here’s Opa walking in front of the Boston Library…Here he is in his old office: do you remember his old studio?” I was watching the scenes, but then also panning to see the expressions on the faces of the others. We were young and old, shuttling between English and Latvian…

The moment that reached me most, I see this now as I look back, was what in filmic terms was a kind of throwaway moment. My father is riding in a car, his profile shown against the Riga skyline and the Daugava River, the Latvian Library somewhere in the distant background. He is talking about his idea of homeland, confessing that for all his years in America, it has never felt like home. He says he longs for the nature of his youth, the trees and fields and trees, the rivers that, as he puts it, move so very slowly.

meet the author

Sven Birkerts

Sven Birkerts is the Editor of the literary journal AGNI based at Boston University. Author of ten books of essays and memoir, he is the former Director of the Bennington Writing Seminars.

share

Subscribe to our newsletter