Prose

The Oldest House in the World

‘I like this house,’ said Tolly. ’It’s like living in a book that keeps coming true.’ - Lucy M. Boston, The Chimneys of Green Knowe, 1958

Photo credit: Poppy Berry

A few years back, a friend had given me a book called The Children of Green Knowe by Lucy M. Boston. First published in 1954, this edition was a smart Faber Children’s Classic reprint. To my shame, I had never heard of the author.

The story centres around a little boy called Tolly and his great-grandmother, Mrs Oldknow, who lives in an ancient, enchanted, haunted house: the ‘Green Knowe’ of the title. The writing is so vivid and the illustrations (by Peter Boston, the author’s son) so precise, it really felt like I was there – in the house, alongside the characters. When I turned the last page and found that this was a real house, with a telephone number – and a fax! – it was like getting to the end of Alice in Wonderland and finding a message from the White Rabbit giving me directions.

So I called. Lucy Boston’s daughter-in-law Diana picked up. We chatted for while, fixed a date, and, a few days later, I got in my car and set off towards Cambridgeshire.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, it was almost destroyed by a great fire that would have razed a lesser house to the ground.

The Manor at Hemingford Grey stands on a bend in the River Ouse on the edge of the village, Hemingford Grey. There are neither National Trust signposts, nor is there a symbol on your Ordnance Survey map. It’s easy to miss the oldest house in the world.

When the stones for the walls were first quarried, humans were just one of the large mammal species hereabouts sharing the wooded landscape with wild boar, red deer, fallow deer, beavers, and even, a little further north, wolves and brown bear.

As near as can be established, the house was built in 1120 ad: just fifty-four years after William the Conqueror died at the Battle of Hastings. This house had weathered four-hundred-and-fifty winters before Shakespeare was even born.

It’s possible that older houses may still exist. There are certainly older structures – churches, castles, abbeys, temples – but what makes this house unique is that for all of its long life, it has been a home. Its walls are steeped in nine hundred years of idle domestic chatter and passionate sweet nothings, the scratch and chirrup of pets and pests, the first cry of a newborn and that same person’s last breath, generation after generation.

At its grandest, it was a large-fronted, many-chimneyed Regency manor house. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, it was almost destroyed by a great fire that would have razed a lesser house to the ground. The outer shell was scorched away, but the flames could not breach the three-foot-thick Saxon stone walls at its core, and the house was saved.

In 1939, Lucy Boston returned from Europe where she had been learning to paint, but “Mussolini pushed me out of Italy and Hitler out of Austria,” she notes. Lucy was staying in flat in Cambridge, where her son was studying. By chance she heard that there was a house for sale in Hemingford Grey and recalled seeing the Manor, just once, fleetingly as she punted along the river many years before, “a semi-derelict Georgian farm house, lived in joylessly, if at all.” On an impulse, she marched up to the front door and asked the startled owners if it was for sale. They had only just decided to sell up – hadn’t even put it on the market – and her appearance seemed like a gift from God.

“Looking back now, it is hard to know why I acted with such certainty and passion. It was like falling in love. I was in my late forties, I knew not a soul in the district and was going to live alone in this overwhelming atmosphere.”

Overlooking its faults and forgiving its many eccentricities, this fiercely independent divorcée moved in and began to explore. The house had been patched and spliced and chopped up and boarded over as successive generations had adapted it to their times and needs. The southern half had been subdivided into “pokey low-ceilinged ill-shaped rooms on different levels” including a guest room painted dark brown and shaped “like a pencil box, long, low and narrow, into which one descended as into a tomb”. And up in the eaves, a tiny servant’s bedroom, which was reached via “a corkscrew staircase through a two-foot square hole at floor level, underneath a tie-beam,” such that (Lucy adds with ghoulish relish), “the unfortunate woman sleeping there would know that anything coming into her room during the night must drag itself in on all fours.”

In Lucy, the house found someone who could strip away the accretion of centuries and restore it– not to its ‘former glory’ or anything so grand or superficial as that – but restore it unto itself, perhaps. And in the house, Lucy found the love of her life, the gateway to the past, a place profoundly connected with deep mysteries: time, mortality, the natural and the supernatural, the self and the other. “All my water is drawn from one well,” she wrote. “I am obsessed by my house. It is in the highest degree a thing to be loved.”

•••

The previous owners reassured Lucy that they had explored the house and found all there was to find. She was unconvinced. “Are you psychic?” they asked. “Why, have you a ghost?” she replied, and they all laughed.

She consulted architects and antiquarians, historians and builders, and then set to, armed with a pickaxe. She knew the house was old – local records show that the builder, Payne Osmundsen, died in 1154 – but had no idea, really, what lay underneath the walls: what shape would reveal itself, what hidden treasures of light and form, or what sleeping horrors might be shaken loose of their millennial slumbers.

Helped by her son, Lucy embarked on a restoration project that owed more to archaeology than interior decoration. They stripped off wallpaper – in some places over a foot thick – counting back through the years as you would count the rings of a tree. On her hands and knees, she peered beneath an old cupboard and could just make out what looked like the base of a column. It takes guts to dismantle a Jacobean cupboard, but once she had, a Norman fireplace was revealed. A simple arc hewn from local Barnack stone, slender columns on either side standing sentinel: marked as though the mason had lifted his chisel clear just moments before. Mother and son sawed and chipped their way through the centuries: Georgian doorways revealed Norman window frames; they uncovered arrow slits behind solid walls, fireplaces under staircases, hidden windows and unexpected staircases, and doorways halfway up walls. Off the dining room, they discovered a mysterious door, apparently leading nowhere and bricked up on both sides, painted with a sinister moonlight scene “much blackened and so obscure that one guessed what was going on more by the frisson it gave than anything actually discerned.”

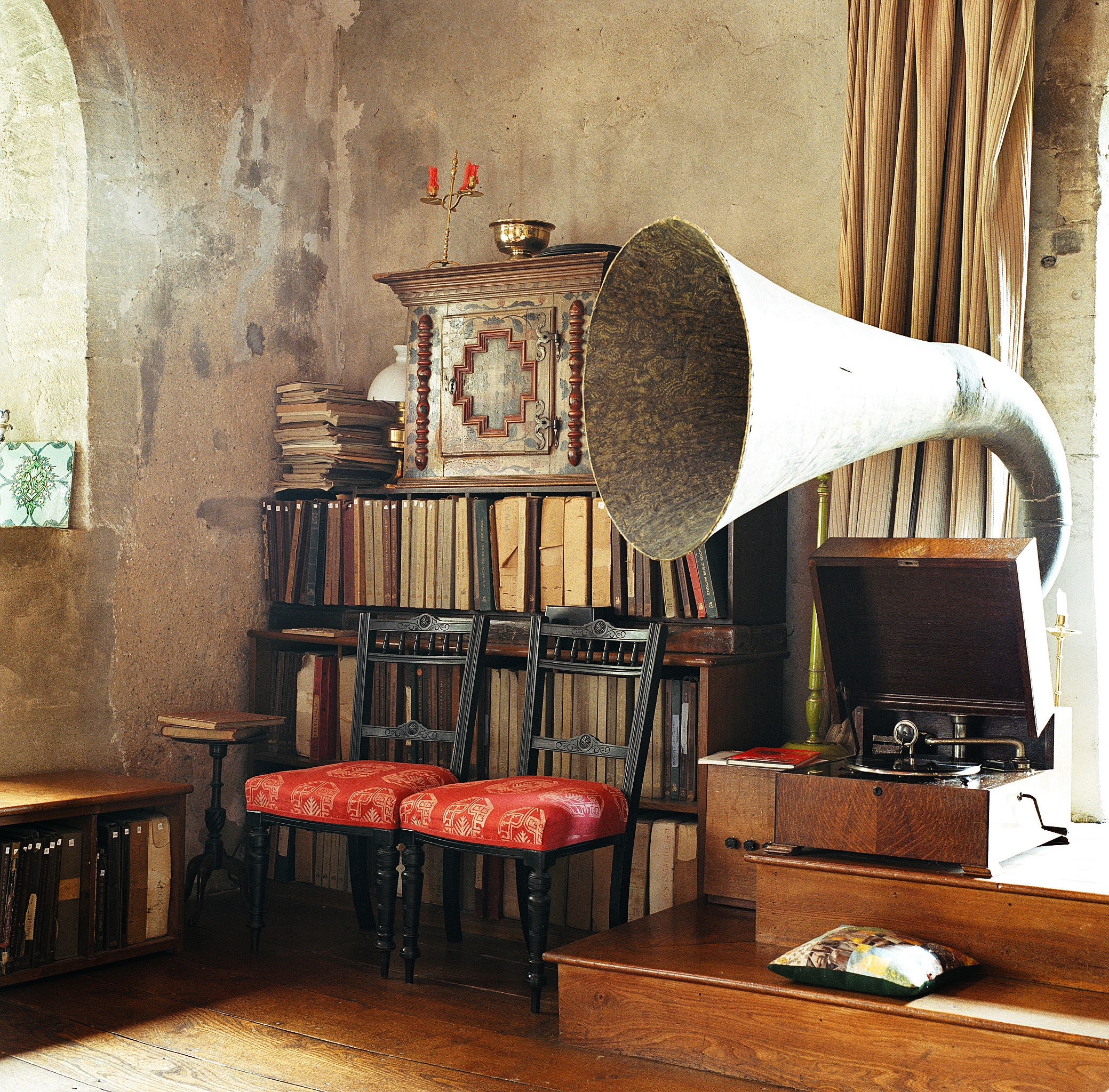

Photo credit: Poppy Berry

They took the house apart, brick by brick, stone by stone, and rebuilt it over a period of two-and-a-half years. At the high point of its demolition, Lucy would camp downstairs in the one room left habitable. With the roof off, the windows glassless and the walls broken down, the surrounding countryside and its inhabitants streamed in:

“Butterflies fanned themselves on quarry-like sections of wall, birds and bees flew in at one side and out at the other… I was living like a rabbit in its hole under the rubble, and I was absolutely happy. There was blackbird song and tumbling water, rising mists over the riverbed and the call of owls. The smell of old dust and builders was an essential detail with its own invigorating promise.”

Even once the restoration was complete, something wild remained:

“The walls seemed to have forgotten that they were ever quarried out of their own place and carried away. They had settled down to being simply stone again, reared up here by some natural action, smoothed and welded by sheer age, so that even when one came in at night and shut the doors and drew the curtains, the wildness of the earth was not shut out.”

Like John Ruskin, Lucy believed in the value of ruins, in celebrating rather that disguising the ‘ravages’ of time:

“The greatest glory of a building is not in its stones, not in its gold. Its glory is in its Age, and in that deep sense of voiceful-ness, of stern watching, of mysterious sympathy, nay, even of approval or condemnation, which we feel in walls that have long been washed by the passing waves of humanity.”

The house in the story admits the creatures of the wild as readily as did the real house with its rafters open to the sky.

Living at The Manor must have been like living on the beach, the ebb and flow of those waves hissing and sighing in your ears, everything created and eroded simultaneously – the cliffs to rocks, the rocks to pebbles, the pebbles to shale, the shale to sand…

•••

In the first of the Green Knowe books (a series of six novels published between 1954 and 1976), Tolly travels to the house for the first time to meet his great-grandmother, Mrs Oldknow, a sprightly and unconventional octogenarian with more than a passing resemblance to the author herself. Tolly arrives during a flood, and the house appears to him a kind of Noah’s ark. He feeds the wild birds standing on the kitchen doorstep holding up fingers covered with margarine and breadcrumbs. The house in the story admits the creatures of the wild as readily as did the real house with its rafters open to the sky.

Tolly is young, and he is lonely: a potent combination. He imagines that the old rockinghorse in his bedroom is alive:

“‘Do you know,’ he said, ‘when I was lying in bed with my eyes shut I could hear the horse go creak-croak just like this? But when I opened my eyes it was quite still.’

‘And did the mouse squeak under your pillow, and did the china dogs bark?’

‘No,’ said Tolly. ‘Do they?’

Mrs Oldknow laughed. ‘You seem ready for anything, that’s something,’ she said.”

The house plays you double, and your ghost walks in your shoes as you step across the threshold.

The lively imagination of the lonely boy conjures up the departed spirits of the houses’ previous tenants: Linnet, Alexander, and Toby – three children who died in the Great Plague of 1665, whose portraits stand over the fireplace in the dining room. When I visited the house, I didn’t see their portrait but up in the bedroom, their toys were very much in evidence: a sword, a flute, a carved Japanese mouse, china dogs on the dressing table, old ivory dominoes, and a wicker birdcage hanging, empty, from the rafters. “They’re not really that old,” Diana explained, patting the rockinghorse (though, given where we were, of course, that was relative). “Some of them are from Lucy’s own childhood; others have been collected or donated by people over the years.” She pointed out one of the horse’s ears, chipped where a child had ridden it so hard it had tipped right over.

When Tolly first enters the house, he is momentarily confused by the mirrors in the hallway. “Everything is twice,” he exclaims. I felt the same. I knew where the Music Room was, where the staircase twisted, how the French windows in the drawing room were placed – I’d read my way through the house before stepping foot into it. I recognised the ebony mouse, the china dogs, the laughing faces of the carved wooden cherubs up near the ceiling in the hallway from Peter Boston’s eerie lino-cut-like black and white drawing. There is an overwhelming sense of déjà vu. The house plays you double, and your ghost walks in your shoes as you step across the threshold. The house is, as Lucy Boston warned, both “haunted and a haunter”, but I never expected to be possessed myself.

The toys seem to be particularly potent conductors of this mysterious power – perhaps because, by their very nature, they have already been ‘bought to life’ once. In the hands of a child, a simplest of toys quickly passes from inert objecthood to conscious being. But the house is full of other such things which seem equally charged: the ancient iron hook hanging above the fireplace, the lacquered Russian doll on the windowsill, the huge Chinese lampshade that hangs like a lonely moon above your head.

The things here are not things in a museum. The house is not dead but living and lived in. The chairs are for sitting on; the umbrella stand at the door there to catch the drips; hooks are for coats; bootbrushes are for wellies; toys are to play with; patchwork quilts are to warm you on a cold winters’ night. Wouldn’t you, dying, want to be at home? Wouldn’t you, dear departed soul, leave fragments of your most intimate, shattered self lodged in the physical stuff of your life – that painted box, those shoes, your favourite armchair?

Why wouldn’t Linnet skip lightly across centuries to flip the pages of her favourite book and Alexander play his flute? Up in the attic bedroom, there’s movement in the room; as you turn, something is half-glimpsed from just beyond your field of vision. Perhaps it’s just a breeze from the river coming through the open window.

I am not sure if I believe in ghosts, but I am sure that if they exist at all, they are not disembodied shades that wander randomly through space and time but are anchored to particular things, particular places. The longer I spent in the house, the more convinced I became that the material objects that populate a life retain traces of that life, becoming semi-animate themselves while conferring a subtle afterlife upon their owners. This is intimately to do with touch and texture; it is deeply connected to the quality of the thing, not just that of the person. I think of things that have had a previous life – biodegradables like wood, cloth, stone – eroding naturally with the passage of time, carrying within themselves some vestige of their previous form. Concrete, plastic, PVC do not age in this way. They may be impervious to more than just the natural elements; perhaps the supernatural is, also.

A picture hanging over the fireplace in the dining room at first appears to be a fairly unremarkable eighteenth-century etching – a manor house up on the hill, ladies and gentlemen on horseback setting off for a hunt. Then I peered closer and realized that the whole thing was stitched from human hair. As Mrs Oldknow remarks to an inquisitive neighbour in An Enemy at Green Knowe (1964), “I don’t want comfortable pictures. I prefer them to have a nip of otherness, like life. In a house like this there is room for questions as well as answers.”

Often, they would be interrupted by a knock on the door – only to find no one there.

Nowhere is the ‘nip of otherness’ felt so strongly as in the Music Room. It was the restoration of this part of the house that seemed to set free its most unhappy spirits. Once it was done, the room seemed to breathe easier, and though hauntings there were aplenty, none of them were of the threatening kind. With its deep recessed window ledges, bare stone walls and high ceiling of lime plaster on rush, the room has all the grandeur of a castle banquet hall, or a church nave, yet in the homely proportions of a large living room. It resonated with “a profound, contained and powerful silence… an intense stillness that suggests an awaited revelation.” During the Second World War, Lucy and her long-time companion, the painter Elisabeth Vellacott, used to hold musical evenings here for the squaddies stationed at nearby RAF Wyton. Twice a week for the duration of the war, airmen would gather to listen to music played on the gramophone, as the bombers flew overhead towards France:

“…I have only twice in any concert hall before or since experienced music where the company listening generated such cumulative intensity as we did then.... perhaps it was the timeless enclave of the room when time was so short and there might be no tomorrow. I am sure the long past of the house was a resting place for those who had, as they said, no future.”

Often, they would be interrupted by a knock on the door – only to find no one there. This continued for several years after the war had ended, and Lucy always assumed that it must have been “the shadow memory, or haunting wish of a lost airman.”

Today’s guests to the house are treated to a few bars of Mozart’s clarinet concerto, played on the wind-up gramophone whose vast trumpet dominates the room like a crouching beast in one corner. The needle is made from a splinter of bamboo; the trumpet is papier maché painted to look like leather, the disk a heavy slab of shellac. The sound ought to be a mess of scratch, hiss, and splutter. But it emerges clear and powerful as though the clarinettist were standing in the room himself, lungs, and lips, and fingers, and reed, and body, sending a surge of music into the still air.

At the end of our tour, Diana picked up a clear glass bottle and held it out to me. It was stoppered and empty, and neatly labelled ‘Time’. “Peter asked me what I most wanted for my birthday,” she said. “And I said, oh – time. I never seem to have enough of that.” She put it back on the shelf with a half smile.

Well into her nineties, Lucy finally gave in to Peter and Diana’s insistence that she at least install electric heaters in the house. But, on the morning they were to have been delivered, rang them to say that she “would rather die of cold in the twelfth century than be warm in the twentieth”, and would they please cancel the order. They did, and she finally died in the home that she loved and which, I have no doubt, her spirit still inhabits, on 25 May 1990 aged 97.

meet the author

Anita Roy

Anita Roy holds an MA in Travel and Nature Writing from the Bath Spa University, and wrote and illustrated A Year in Kingcombe: The Wildflower Meadows of Dorset. She is the author of Gravepyres School for the Recently Deceased, a fantasy [...]

Subscribe to our newsletter